Being an ardent traveller myself, I was naturally impatient to step out upon the journeys of my ‘passionate travellers’. But self-discipline was necessary. Though in many cases I was already familiar with the landscapes they traversed, before describing their incredible experiences and telling the stories of what drove them I had first to understand their individual characters.

Being an ardent traveller myself, I was naturally impatient to step out upon the journeys of my ‘passionate travellers’. But self-discipline was necessary. Though in many cases I was already familiar with the landscapes they traversed, before describing their incredible experiences and telling the stories of what drove them I had first to understand their individual characters.

After poring over biographies, autobiographies, correspondence, and travel accounts it occurred to me that, however a traveller treated their hosts, their relationship with their guide would give deeper character insights. As one perceptive reviewer observed, though their courage and enterprise almost took one’s breath away, they would not all have made pleasant travelling companions.

When travelling far from home, we may adopt a new ‘persona’, take advantage of release from social obligations of our own culture to experiment with different behaviour. But the relationship with a guide, the balancing act between the hirer’s authority and our utter dependence – the trust required, even with our lives – touches the inner core of our personality.

I hope my safety never depends on the sort of swashbuckling guide who led the aging Haiku poet, Matsuo Bashō, along the unmarked, treacherous approaches through Japan’s Dewa Mountains.

‘Bashō had hired a robust, sword-swinging young guide. After days of stumbling along in darkness through dense bamboo thickets and across tumbling rivers “in a cold sweat” of fear, Bashō’s relief at reaching their destination was palpable. The youth heartily congratulated him with some surprise, explaining that all previous travellers he had led through the mountains had met with accidents.’ (Passionate Travellers)

In life-threatening landscapes, there is much to be said for older guides. Their own longevity demonstrates a certain level of competence to survive.

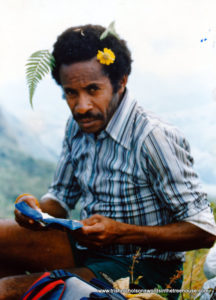

The day before three male companions and I embarked on the hair-raising trek from Oksapmin to Lake Kopiago in Papua New Guinea, we had negotiated a price with three local men to act as guides. Living and working in the country on rural development projects we understood pay levels and had offered a generous rate. We would carry food in our backpacks and cook for the guides as well as ourselves.

But when the men upped the price as we assembled the next morning, we decided to start on our own and trust to finding guides in villages we would pass. We hadn’t gone far when Thomas, the older man (probably in his fifties) said he would take us for the agreed rate and find two others on the way. It was a blessing that he did.

The route was not a marked trail. Beyond local paths linking villages and a rotting vine bridge across the surging waters of the Strickland gorge, there were only precipitous rock outcrops and dense mountain forest. One of our party became ill, but there was no possibility of turning back; we had to reach our destination as quickly as possible for him to receive treatment. We kept going even after dark, scrabbling down steep slippery slopes through the forest, feeling as if we were descending to the bowels of the earth. And when Thomas insisted on stopping at intervals to pray for our safety, we fully appreciated the danger we were in.

It proved to be a tougher experience than even Thomas had imagined. In recognition of this, when we arrived at Lake Kopiago and paid him along with the two other guides he had hired, we also bought them air tickets to their home villages to save them walking back.

Reflecting that night, I realised that the only reason Thomas had agreed to join us was to save four young fools from killing themselves. (You can follow the trek in detail in Inside the Crocodile: the Papua New Guinea Journals.)

An equally dependable guide was essential for Isabella Bird’s three-month journey along the length of nineteenth-century Japan from Tokyo to the Indigenous Ainu communities in Yezo (Hokkaido). Not only would he have to arrange routes, transport and accommodation through some of the ‘wildest’ parts of the country previously unvisited by Europeans, and certainly not by a European woman, but also to act as interpreter in a wide range of social situations.

Although Isabella had failed to find any other competent contender, she had had reservations about hiring Ito: a youth of eighteen years, he presented himself without references and in a disconcertingly bold manner. But he claimed knowledge of local botany and knew enough English for them to understand each other. She knew it was inevitable that he would, whenever possible, work ‘a squeeze’ with her money – agree a price with a supplier and then split the overcharge – but she accepted it within reason as customary.

Despite being shaken to his core and even driven to tears by the hazardous conditions, the filth, the bed bugs and the lack of decent food, Ito was efficient and remained faithful to Isabella. On her part, she tolerated his bossiness, and turned a blind eye on his imperious manner towards his fellow countrymen. They had accommodated to each other for mutual benefit, and it was only on reaching Yezo that Isabella realised how lucky she had been. She discovered there that Ito had abandoned his previous employer – a European botanist – without notice, and his irate master was demanding his return.

Michel de Montaigne was also relaxed about money during his European tour in 1580. He left his servants to pay bills from the cash-box that travelled with them and never asked for receipts, recognising their right to “the gleaner’s share”. But he did not suffer fools gladly. When it became clear that the guide he hired in Germany knew little about the area and lacked the intellect for stimulating conversation, he called him a “blockhead” and dismissed him.

[Pic: Getguided blog]

Ida Pfeiffer travelled on a strict budget. She could not afford to allow a “gleaner’s share” and would have been horrified at the mere suggestion, indignant as she was about the price of everything and ever suspicious of being overcharged. Travelling in Iceland, in 1845, Ida paid “an outrageous price” to hire an experienced mountain guide to climb Mount Hekla. But according to Ida, no one had ascended Hekla in the previous nine years, so it seems a bit hard to accuse the guide of profiteering.

From the height of her fastidious Viennese upbringing, Ida Pfeiffer was appalled by the “uncleanliness” and “laziness” of Iceland’s peasantry in general, and of her guides in particular who she claimed were invariably drunk. Ida does not name her guides and tells us nothing about them, even the one who led her safely through hazardous terrain for three weeks. It’s as if, to her, guides were on a par with the horses.

It is difficult to understand how Ida could take so little interest in the people on whom her survival depended. But a skilled guide does not always let their charges know the dangers they have avoided, and Ida’s consuming interest was landscape, not people. The only guide she did praise, though still unnamed, was an elderly woman hired on her arrival at Haverford to take her the nine miles to Reykjavik.

She is about seventy years of age, but looks scarcely fifty; her head is surrounded by tresses of rich fair hair. She is dressed like a man, undertakes, in the capacity of messenger, the longest and most fatiguing journeys; rows a boat as skilfully as the most practised fisherman; and fulfils all her missions quicker and more exactly than a man, for she does not keep up so good an understanding with the brandy-bottle. [Ida Pfeiffer]

In contrast, the Christian missionary, Mildred Cable, who spent the 1920s travelling up and down the Silk Road and across the Gobi Desert in a high-wheeled Kansu cart, took an intense interest in everyone she met. She names all her guides, drivers and helpers, often telling us also about their circumstances and families. Mildred’s friendly compassion, though genuine, was not entirely disinterested: to each person she met Mildred told the Christian message and pressed a gospel or two upon them, even the guardian of the ancient Buddhist caves at Dunhuang. To Mildred, Buddhism was at best misguided, at worst, evil. Engagement was her ‘weapon’ of choice and her guides were a captive audience.

And before I sign off, I cannot resist an affectionate mention of one of our guides on a high altitude trek in Bhutan. He was a yak herder who supplemented his income during the trekking season. Much to his amusement we nicknamed him ‘Genghis’, but his somewhat forbidding expression concealed a gentle, generous heart and an irrepressible sense of humour. It was Genghis who brewed a traditional herbal concoction that halted my high fever and enabled me to continue the trek. Abroad as at home, it is wise to seek beyond outward appearances.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History

Also available as an eBook from your favrourite digital supplier.