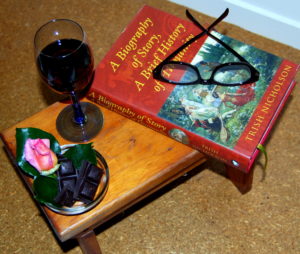

The power of Scheherazade’s storytelling saves her life. The characters, too, often gain redemption through telling their stories. Even Schahriar, the sultan who holds Scheherazade’s life in the balance each day, is freed from his self-defeating obsession against women by listening to her stories. [A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity]

Where do stories come from? Why have some stories stayed with us for thousands of years?

We’ve been asking questions since we possessed language to speak. From how to fulfil basic needs for food and safety, to a deeper curiosity: the ‘why’ of all things. And the question beloved equally by scientists and storytellers: What if? Both search for meaning in better stories.

Each of us in our own way longs for meaning, for resolution to our inner conflicts and those that surround us, for a pathway to the art of living, and for hope. We strive to achieve these through our inner narrative fed by the stories of others: “Each of us … constructs and lives a ‘narrative’ and is defined by this narrative.” (Oliver Sacks) We are all storytellers.

Sharing stories is what defines us as human beings. In the first light of their humanity, our ancient forebears created names for things and for each other, so they could think and talk about them. Objects, places and persons once named acquire a relationship to us, a character, a past, a present and a possible future – they begin to inhabit their own story. Storytelling shared this knowledge in ways that it would be remembered and passed on through generations.

Sharing stories is what defines us as human beings. In the first light of their humanity, our ancient forebears created names for things and for each other, so they could think and talk about them. Objects, places and persons once named acquire a relationship to us, a character, a past, a present and a possible future – they begin to inhabit their own story. Storytelling shared this knowledge in ways that it would be remembered and passed on through generations.

Vital to the survival of early humans was recognition of their dependence on the natural environment: the elements that offered succour even as they threatened; the challenging landscapes through which they travelled; the plants and animals they foraged and hunted. In ancient tales of Indigenous peoples, animals play important roles: the Sanema-Yanomami peoples of Venezuela were given fire by the humming bird, who darted into the mouth of the fearsome caiman to capture burning embers and place them in the sacred Puloi tree – whose twigs the Sanema-Yanomami rub together to make a fire spark.

Storytellers passed on accumulated knowledge that encouraged early hunters and gatherers to co-operate with each other; those who did flourished despite the hardships and trials of raw nature. These stories contained the wisdom for survival – an understanding that most of us have lost along with the words but now desperately need.

Storytellers passed on accumulated knowledge that encouraged early hunters and gatherers to co-operate with each other; those who did flourished despite the hardships and trials of raw nature. These stories contained the wisdom for survival – an understanding that most of us have lost along with the words but now desperately need.

Accounts of great floods are among the oldest stories and they may be universal. This would not be surprising since the geological record supports widespread flooding in earth’s recent history from receding ice sheets, or from massive volcanic action that disrupted the landscape of an entire continent. Australian Aboriginal stories of inundations have been traced back to rising sea levels 10,000 years ago. In Indonesia, the Moken, the Sea People of Aceh, held on to their myth of the ‘seventh wave’; the wisdom it held saved their lives and enabled them to rescue others during the terrible tsunami on Christmas Day in 2004.

But stories, myths, epics, fairytales and legends have multiple roles. A seemingly simple tale is multi-layered, multi-dimensional. Stories define our identity; establish a past and the hope of a future; provide models of behaviour through the actions of their heroes, heroines and villains; reassure us of our humanity; inform and expand our inner lives, our emotions and empathy; and, of course, they must enthral and entertain to ensure their own survival.

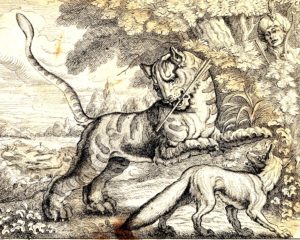

In other ancient Indigenous stories the characteristics of specific animals – brave, skittish, cunning, clever, dangerous – are related to human behaviour, encouraged or cautioned against as the plots unfold. Our inheritance is the ‘beast fable’ found in most cultures. We are, perhaps, more familiar with Aesop’s fables, but his inspiration marked a high point in a tradition reaching back millennia and still existing in various forms throughout the world. As a source of essential truths, their appeal touched all levels of society: Socrates enlivened his time in confinement by creating verse forms of the fables he remembered.

In other ancient Indigenous stories the characteristics of specific animals – brave, skittish, cunning, clever, dangerous – are related to human behaviour, encouraged or cautioned against as the plots unfold. Our inheritance is the ‘beast fable’ found in most cultures. We are, perhaps, more familiar with Aesop’s fables, but his inspiration marked a high point in a tradition reaching back millennia and still existing in various forms throughout the world. As a source of essential truths, their appeal touched all levels of society: Socrates enlivened his time in confinement by creating verse forms of the fables he remembered.

And practically every culture tells a migration story. It may be expressed in the movement of heavenly bodies; the arrival of strangers who brought some precious benefit; the wanderings of adventurous individuals; or in a tribe’s search for new lands. In a Celtic myth describing the peopling of Ireland (in the Book of Conquests), families of Nemeds landed on the western shore after migrating from Scythia – around the Caspian Sea in the centre of Eurasia – a history that genome research has since proven to have taken place around 3,000 BCE.

Norse mythology recalls the long journey of Odin and his family, also from the Caspian, sailing north up the Volga River – the same route along which Vikings later traded and raided in the opposite direction. Māori culture, too, is rich in tales of exploration in their peopling of the Pacific. We are a migratory species. A moment’s reflection will reveal how often journeys, real and metaphorical, flow in and out of our favourite stories,

Norse mythology recalls the long journey of Odin and his family, also from the Caspian, sailing north up the Volga River – the same route along which Vikings later traded and raided in the opposite direction. Māori culture, too, is rich in tales of exploration in their peopling of the Pacific. We are a migratory species. A moment’s reflection will reveal how often journeys, real and metaphorical, flow in and out of our favourite stories,

Interwoven through all of these ancient tales are stories of coming of age, of opportunity, bravery and cowardice, of risks and riches, of growing old, of battles won and lost, and of love. Oral storytellers still enrich our tales with their unique voices and gestures, enchanting each audience anew.

But whether stories in all their immense variety are told orally, in texts, on stage, or on screen, and however old or new they are, they all have a common core: conflict. Challenges faced or failed, and the transformations that result. Struggle is the human condition.

Apart from the struggle for survival between the bounties and threats of our natural environment, the greatest source of conflict has always been that between ourselves and others because we are social beings: conflict between the needs of the individual and the group; competition between and within generations, not only for resources but for recognition, power, love; opposing forces of different groups; and the inner conflicts of each of us balancing sometimes incompatible desires. Through stories we live many lives, inhabit new places. Such is the power of story.

Beginning writers are often advised that ‘where there is no conflict there is no story.’ Tension must be felt and ultimately resolved. Of all the multiple roles that stories perform, the recognition and resolution of conflict is arguably the most significant to us and to the nourishment of our inner narrative.

Although the implications of conflict may have been different for our ancient ancestors – expulsion of a person from their foraging group, for example, was virtually a death sentence – we still face those same sources of conflict. The same act of ‘naming’ allows us to think and speak of our darkest fears, to address the unknown and the unknowable.

As humans, our needs are complex, our desires even more so. We still need stories to provide meaning, resolution and hope. That is why elements of so many ancient tales are still with us in some form after thousands of years. Today’s stories bear the ‘genes’ of all our stories past. Chinua Achebe understood this, “The story is our escort; without it, we are blind.”

It may not be true that ‘everyone has a book in them’, but each of us has our own story to tell, to share, to add to the pool of human wisdom upon which we draw to learn the art of living. Our future survival depends on it.

Trish Nicholson is the author of A Biography of Story, a Brief History of Humanity, the first global history of storytelling. You can read a review here

[The text of this post was originally published on Anne Stormont’s (@writeanne) website, Put It In Writing, as part of her 2019 Virtual Book Festival]