A forest is never complete; nothing in nature is ever truly finished. All living things exist in a state of transition, of becoming and, therefore, of perpetual uncertainty and change – and not only sentient beings but the land as well.

We may think of earth as immutable, a permanent foundation, solid ground beneath our feet, but every natural feature bears the heritage of its unique deep-time story which continues in transition. Into each landscape we etch our own lives, for good or ill, and write our own tales. [The Five Acre Forest]

Trees etch their lives into the landscape too, and while the nature of the ground beneath them will affect how they grow, so their own activities make changes in the world below their roots. Interactions between living organisms and inanimate material such as rock or sand are as important as those between living beings. All of these interactions are the engine of reciprocity that spins nature’s web of life. Life is more complex than panel games: animal, vegetable and mineral are all in this together.

As an example, I’d like to tell you the story of Podzol, but first, we need a bit of back-story.

I planted the five acre forest on a neglected old sand dune that had, with others, migrated inland from the shore, while the shoreline itself edged further out into the sea. And dotted over this area between the inland dunes and the coastline are small freshwater dune lakes and swamps, the burial grounds of ancient forests that perished here 50,000 years ago. The Dune on which the forest is planted, lies between a dune lake on one side, and a kauri swamp on the other.

The Dune is at the southern end of a long narrow sand spit, a tombolo about 100 kilometres in length, created over millennia by two sets of ‘ancestors’: ‘the old sea-salt of a great-great-grandfather … the turbulent sea’, and ‘the more disruptive side of the family’, the volcanoes. The creation of the tombolo is an amazing story that I relate in The Five Acre Forest but I will give you here the briefest of outlines.

In Māori mythology, the cunning culture hero, Māui, fished this piece of land, shaped like a whale’s fluke, from the bottom of the ocean with a magic fish hook fashioned from the bone of an ancestress. The geological facts are just as enthralling because, allowing for poetic licence that is pretty much what happened.

For millions of years after Zealandia broke away from the great continental plate, Gondwana, the land was repeatedly submerged and uplifted while the earth shook and volcanoes spewed lava over the landscape. Amid the tumult, mountains were raised, were eroded by wind and rain, and were replaced by more mountains with each new seismic drama.

After the last great uplift, about 3 million years ago, the sea to the north of Zealandia was dotted with tiny isolated rocky islands – remnants of ancient volcanoes – while major eruptions continued on the mainland of Northland. Over time, eroded volcanic debris was washed into the rivers and carried out to sea towards the tiny rocky islands.

From that time, as rain and wind eroded the volcanic landscape of central North Island, rivers washed eroded particles into the sea to west and east, and this sediment was carried north by prevailing sea currents. Sand and debris accumulated along the shallow coastlines. Snagged on rocks and built up in bays and inlets, it began to form coastal dunes … By a million years ago, more dunes had joined these pioneers, forming a not-quite-continuous band like the curved rib of a coat-hanger… [The Five Acre Forest]

Until, eventually, new land was laid from the ocean-borne sediments, joining all those rocky islands into a continuous stretch of sand, and the tombolo was formed. Indeed, it is still forming because the ocean takes away as well as gives sand to the shore, orchestrated by weather, currents, and changing sea levels.

While I have been sitting here on a sand dune overlooking the beach, musing on the wonders of nature that created this strip of land, a playful breeze has thrown soft sand over my feet. And I marvel at the tiny particles of ancient volcanoes caught between my toes. It seems equally wonderful to me that modern scientists can analyse the minerals in these sand grains and estimate not only their age, but also the likely volcano that gave birth to them as lava and ash before they solidified and were worn down to a single grain. [The Five Acre Forest]

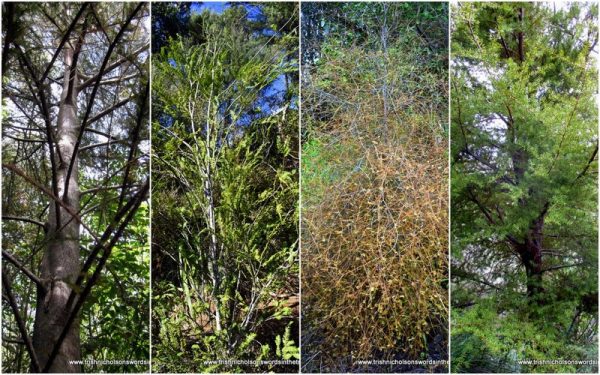

Which brings us around to the story of Podzol. Trees from the primeval conifer forests of Gondwana continued to flourish on Zealandia (as their descendents now do in The Five Acre Forest). Those of the botanical family, Podocarpaceae, include our mighty forest trees: kahikatea, white pine (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides); miro (Prumnopitys ferruginea); matai, black pine (Prumnopitys taxifolia); totara (Podocarpus totara); rimu, red pine (Dacrydium cupressinum); toatoa, celery pine (Phyllocladus toatoa); and kawaka (Libocedrus plumose). But the mightiest is our only endemic member of the even older coniferous Araucariaceae family: kauri (Agathis australis).

To varying degrees, they are all adapted to poor, acidic soils and live in a reciprocal relationship with the nutrient-poor but mineral-rich volcanic sands which formed the tombolo. But it was kauri forests that clothed the area around the Dune, and whose remains lay under nearby swamps and dune lakes for the last 50,000 years, so it is they who will take our story forward.

[T]he sediment, swept along northern sea currents to create our beaches and dunes, consists mostly of silica (quartz, ground glass) but also traces of aluminium, iron and magnesium which the trees process and shed as organic material during their long life-cycle. Over millennia, rain leaches these organic minerals out of the soil, freeing them to percolate down where they accumulate and consolidate into an impervious layer, a hard, uneven pan of varying depth which may be several metres below the surface. [The Five Acre Forest]

The results of this interaction between the trees and the ground beneath their roots is called podzolisation: it creates the poor, leached, acid soil type called podzol, typical of areas bearing extensive podocarp and other coniferous forests (not only here in the far north of New Zealand but in different climates in other parts of the world. **See footnote).

And the hard pan at lower levels that kauri initiated is the impervious layer that holds the water of the dune lakes, the swamps, and the underground aquifer – water that gives life to plant, animal and human communities on the surface. As I said before: animal, vegetable and mineral are all in this together. Truly, everything is connected.

This has been quite a long story, but I tell it because many people are fazed by the technical language and mind-bending timescales of geology and geomorphology. Yet it is possible to delve between the layers of jargon to gain a general understanding of the patterns and processes that surround us and are part of our lives, even if we are unaware of them. The ground beneath the trees affects the growth of the five acre forest, and the balance between courting and wilding new growth.

Considering the trees of your acquaintance, do you know what ground lies beneath their roots and how they reciprocate?

**Footnote: The word ‘podzol’ is not derived from Podocarp forests, as other conifers can also form the ashy mineral layer that develops into a hard pan. It derives from the Russian “подзо́листая по́чва” (podzolistaya pochva, “under-ashed soil”) where it was identified in Russian forests in the 19th century by Vasily Dokuchaev. ‘Podocarp’ is from the Greek word for ‘foot’, which describes the position of the fruit in leaf axils. (Thanks to Rob Edwards for pointing out the potential for confusion.)

[For anyone interested in a detailed geology of New Zealand’s Northland, I recommend the recent, readable and beautifully illustrated book by Bruce Hayward: Out of the Ocean into the Fire, Geoscience Society of New Zealand, 2017.]If you found pleasure in this post, please be kind and share it with others so they can enjoy it too.

Trish Nicholson is the author of The Five Acre Forest, a personal tale of tree planting that tells the deep-time story of a New Zealand sand-country landscape. A story of the land, of nature, of transformation and reciprocity. And a story of hope.

Trish Nicholson is the author of The Five Acre Forest, a personal tale of tree planting that tells the deep-time story of a New Zealand sand-country landscape. A story of the land, of nature, of transformation and reciprocity. And a story of hope.

ISBN: 978-1-80046-487-2 Natural sciences, 256 pages plus maps and 16 colour plates.

Available in bookshops, direct from the publisher’s online bookshop (UK only), and online worldwide (free delivery), and from all other main online book suppliers.

a fascinating explanation Trish.

Hi Chris, glad you liked the post. The more I dig into research on the past, the more fascinating it becomes, and the clues surround us in the landscape. I look at it all with a different eye now.