We have been global for millennia.

We were ‘global’ thousands of years before air travel and international corporations, or as far as the ‘globe’ was known which amounts to the same thing in courage and curiosity. People and their stories, crafts and goods crossed back and forth linking Asia, Africa, the Middle East and continental Europe more than 5,000 years ago.

While I was writing my history of storytelling, A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, I came across many weird and wonderful true travel tales. I had to leave them out of A Biography of Story because they would have been too much of a diversion, but once I had recovered from creating that magnum opus, I was drawn back to the travel tales and inspired to write, Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History.

The impulse to travel beyond the known has probably been in our DNA since before our first migration out of Africa around 200,000 years ago – a migration that lasted thousands of generations. Indeed, the journeying has never stopped. The ultimate destination is, perhaps, not only a physical one. We can leave that idea hovering on the horizon.

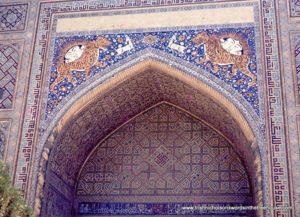

Al-Mas‘udi, a native of Baghdad born sometime before 893 CE (280 HA in the Muslim calendar), gave no fixed address because he was perpetually ‘on the road’ or, more likely, on a camel, especially when following the vast network of trading lanes that made up the Silk Road. He travelled north as far as the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan and Armenia; east through Persia; south to Egypt, India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the African coast to Zanzibar, and west to Syria and the Mediterranean.

But al-Mas‘udi was also a scholar and something of a journalist. He didn’t simply bum around. For his twenty books covering the history, geography and culture of the places he visited, he gleaned information from merchants, locals he met along the way, and other scholars as well as reports of earlier travellers. He reveals the cosmopolitan nature of cities: in the Khazar Kingdom, different supreme judges specialised in resolving disputes according to the various laws of Moslem, Christian, Khazar (who had adopted Judaism at that time) or pagan residents.

Books were rare and expensive in Europe, but Baghdad was ‘book-city’ with over 100 bookshops and operated its own paper factory. Developing techniques the Arabs had learnt from China, they mass produced cheap writing materials, making possible a burgeoning publishing industry of hand-copied manuscripts preserving for us much scholarship of the time.

Al-Mas‘udi’s works received limited attention during his lifetime because he never mastered the art of being concise – 130 chapters and thousands of pages in a single volume proved too daunting for most readers – although he did edit and condense some of his works later in life. His most famous travelogue, Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems (‘Murūj al-dhahab wa ma’ādin al-jawāhir’), amounts to a world encyclopaedia of 365 chapters.

Even games are included in this extract on the reign of el-Bajbud, a Hindu king in India:

“In his reign the game of tables or backgammon was invented. This game shows how one obtains gain, for it is neither the result of sagacity and contrivance, nor is subsistence earned by cleverness in this world…The dice are meant as symbols of fate and the way in which it deals with mankind; for the player who is favoured by luck, will attain in this game what he wishes, whilst the clever and provident is less lucky than another, if the other is favoured by fortune; for gain and good fortune are a mere chance in this world.

In the reign of his successor King Balhit, the game of chess was invented. Al-Mas‘udi recommended the game in preference to backgammon, pointing out that skill determines the winner rather than chance.

And in China, ambitious parents pursued a tough alternative to Eton and Cambridge as a route for their offspring into the upper echelons of the civil service:

“In China eunuchs are appointed in the revenue department and other offices: some parents, therefore, castrate their children, in order that they may rise to power.”

Among other detailed observations is that “the best musk [an ingredient of perfume and an extremely valuable item of trade] comes from Tibet where musk deer feed on aromatic herbs, the essence exported in the bladder in its natural state. Chinese musk is of inferior quality because they adulterate it to make it go further and then bottle it.” (The trade continues despite the fact that musk deer, of the Moschidae family, are now an endangered species.)

As to health, al-Mas‘udi quotes a Hindu poem on the advisability of breaking wind freely whenever the need arises “for restraint is unwholesome”. Though perhaps less so for one’s near companions.

Local fauna are not neglected. In the mountains of Central Asia, man-like monkeys covered in hair are kept by the Tartar kings to test their food for poison, which the monkeys can smell. And a famous war elephant in Kashmir called Monkirkals, was leading eighty elephants from their stable through the outskirts of the city when a woman, surprised by their appearance in a narrow lane, slipped and fell onto her back. Monkirkals turned to block the road, protecting her from the elephants following him, and helped her up with his trunk.

While al-Mas‘udi quotes myths, hearsay, and vignettes of kings and their misdeeds worthy of The Arabian Nights, much of his geographical and historical information is accurate in advance of his time. One of his most prescient comments for our modern times of fake news and corruption of online content is this warning at the beginning of his book:

“Whosoever changes in any way its meaning, removes one of its foundations, corrupts the lustre of its information, covers the splendour of one paragraph, or makes any change or alteration, selection or extract; and whoever ascribes it to another author, may he feel the wrath of God!”

And he goes on at length describing what terrors he hopes that wrath might entail. I have taken care to give due credit. (Extracts from Meadows of Gold are from an English translation by Aloy Sprenger, M. D., available online at Internet Archive.)

Fascinating and entertaining though his accounts are, al-Mas‘udi is not among my twenty-one selected ‘passionate travellers’ for two reason: he records what he sees and hears but does not detail his travel experience, and little is known of his own story. In Passionate Travellers, I reconstruct the inspiring journeys of each of the eight women and thirteen men, so that readers can share their adventures step by step, and relate their personal history to understand what drove them to attempt their quests even at risk of their lives.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History

You can read why I wrote Passionate Travellers, and find out who they are here:

In previous posts in this series you can chuckle over ‘Fleas, Bedbugs and Other Travelling Companions’, and discover ‘How to Detach Unwanted Leeches’.

And read reviews by Sam Law (@readworldbooks) on his book blog Its Good to Read, and by travel writer Valerie Poor (@vallypee on her Memoir Review blog.

My other travel books that might interest you:

Inside the Crocodile: The Papua New Guinea Journals

Journey in Bhutan: Himalayan Trek in the Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon (eBook only)