Before being sucked under the spells of retail elves and their Christmassy shelves, let’s take a not-too-serious look at the meaning of gifts over the ages.

Before being sucked under the spells of retail elves and their Christmassy shelves, let’s take a not-too-serious look at the meaning of gifts over the ages.

The proverb ‘never look a gift-horse in the mouth’ is known across Europe in languages from Icelandic to Russian, but for anyone unfamiliar with this advice, it means we should not judge the intrinsic value of a gift. Experienced horse-dealers amongst you will know that the age and condition of a horse is gauged from its teeth: when you notice that the lavishly gift-wrapped box of chocolates your cousin sent you is nine months beyond its use-by date, you know you’ve been given a useless old nag.

It may be the thought that counts, but what, exactly, were they thinking?

In its purest form, giving is caring with no expectation of reward. It may demand equal commitment in learning to accept graciously. During a hectic working life I dashed off for fleeting visits to a favourite elderly aunt whenever I could. When the time came for me to leave, my aunt would press into my hand a package of squelchy spam sandwiches made with love to protect me from starvation on my 60-minute rail journey home. I could never stomach the sandwiches though I learnt to appreciate the gift with a full heart.

Like storytelling, gift-exchange emerged during the dawn of human history. The gift of an antelope steak given in good faith, accepted with grace, and later reciprocated with a well-knapped spear-head, created whole networks between families, clans and tribes. In time, the exchange of gifts developed into the first trade deals as the relative value of each item was arduously negotiated, but the significance was always more than economic – it created relationships based on trust. Even stories were bartered. Itinerant storytellers have long earned a night’s lodging with a good story, as Odysseus did in Homer’s Odyssey.

Barter remains important in many parts of the world. While living in Papua New Guinea I acquired my treasured collection of clay pots and shells through barter. And travelling in the Amazon, I exchanged my wellington boots for a two-metre poisoned-dart blow-pipe in a Yaguar village (a keep-sake that caused sensational hassles at every airport security check). Both transactions involved forging relationships – telling stories and learning to understand each other.

Barter remains important in many parts of the world. While living in Papua New Guinea I acquired my treasured collection of clay pots and shells through barter. And travelling in the Amazon, I exchanged my wellington boots for a two-metre poisoned-dart blow-pipe in a Yaguar village (a keep-sake that caused sensational hassles at every airport security check). Both transactions involved forging relationships – telling stories and learning to understand each other.

But in the same way that stories multiplied and diversified across the world, so did the forms and meanings of gift-giving.

A Viking chief was expected to be generous to his followers in dispensing loot from raiding expeditions. By gifts of gold to award valour and encourage loyalty, great leaders became known as ‘Ring Givers’. However, evidence of buried gold hoards suggests that some chiefs preferred to hide their ill-gotten gains underground – the Norse equivalent of an off-shore account. Gifts in exchange for loyalty are still a widespread practice, from the discount offered on your store loyalty card to the appointment of corporate raiders to plum jobs in government administrations.

Perhaps the most dramatic ritual gift-giving is the potlach ceremony, developed to a fine art by the Native American Kwakiutl peoples of the north-west coast. Any social or personal milestone provided an excuse for a potlach, but the biggest feasts for the greatest number of guests, the longest speeches and the most lavish gifts were preserved for the installation of a new successor to the chieftaincy. And everyone in the tribe was expected to dig deep to contribute.

Potlach was all about status. The volume of goods distributed boosted the social standing of the giver, as the value of each gift reflected the status of the recipient, and the more guests to witness the transaction the more powerful the event. To fall short in any of these calculations courted political suicide. It requires no stretch of the imagination to see all of this in world leaders’ rounds of state visits funded by hapless tax-payers, not to mention presidential inaugurations.

Gifts often involve a catch. Even Saint Nicholas’ legendary generosity to children, celebrated in the Netherlands on December 5, was conditional upon each child’s past behaviour recorded in the Big Book. The medieval tradition, where Saint Nicholas’ helpers included frightening characters representing Satan, may have been the stick accompanying the carrots. But modern Zwarte Piet is a clownish trickster throwing tiny gingerbread biscuits into the crowd like confetti. As commercial interests focus on December 25th in line with most of Europe, the devil is forgotten and smart kids claim two Christmases.

Most religions recognise the importance of gift-giving either in shared celebration; as sweeteners to the gods; or as a form of wealth distribution. Christians may follow the example of the Three Kings with their Christmas presents, but festive gift-giving features also in the Jewish Hanukkah and Hindu Divali, while giving alms to the needy is a central tenet of both Islamic and Sikh faiths. Although offering a small gift is a daily occurrence for Buddhists, I had not expected to be given an apple by the abbot while visiting a monastery in Bhutan. Luckily, I always take pens and postcards as little presents when travelling and found a spare pen in my pocket to reciprocate.

Most religions recognise the importance of gift-giving either in shared celebration; as sweeteners to the gods; or as a form of wealth distribution. Christians may follow the example of the Three Kings with their Christmas presents, but festive gift-giving features also in the Jewish Hanukkah and Hindu Divali, while giving alms to the needy is a central tenet of both Islamic and Sikh faiths. Although offering a small gift is a daily occurrence for Buddhists, I had not expected to be given an apple by the abbot while visiting a monastery in Bhutan. Luckily, I always take pens and postcards as little presents when travelling and found a spare pen in my pocket to reciprocate.

Exchanging gifts appears to be a universal human practice but cultural awareness is advisable. Social occasions for gift-exchange occur throughout the year in China, but in a culture where maintaining ‘face’ ranks highly, what to give, to whom, when, and exactly how much to put into the ‘little red envelope’ poses an etiquette quagmire to the unwary.

My apologies if these reflections disrupt the Christmas gift-list you had already ticked off during the summer sales.

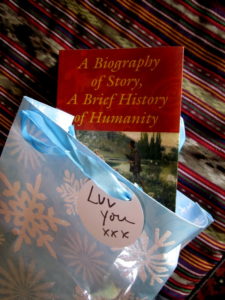

I may be a little biased, but to be on the safe side, I’m giving everyone books this year.

And here are a few suggestions:

For the avid readers and story-lovers in your life: A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity. The only global social-history of storytelling. The power of stories in the comedy and tragedy of human affairs.

Within the UK, you can buy direct from the publisher’s online bookshop with a large discount: https://www.troubador.co.uk/bookshop/history-politics-society/a-biography-of-story-a-brief-history-of-humanity/

or you can order it from your favourite bookshop.

For the real and armchair travellers in the family (all have ebook editions available from your favourite supplier for all devices): Inside the Crocodile: The Papua New Guinea Journals, an adventure in the land of the unexpected. Journey in Bhutan: Himalayan Trek in the Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon, sharing the journey of a lifetime (ebook only), and the latest: Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible journeys in History

And for the wannabe writers of memoir, travel, history, biography or anything else: Writing Your Nonfiction Book: the Complete Guide to Becoming an Author, a step-by-step guide to inspire you from initial idea to researching, planning, writing, editing, publishing and marketing your book.

Have a wonderful bookish Christmas!