Illness while on a long journey can be tricky, especially in remote places with few, if any, medical facilities. Most adventurous travellers pack an emergency medical kit.

Illness while on a long journey can be tricky, especially in remote places with few, if any, medical facilities. Most adventurous travellers pack an emergency medical kit.

How much worse it must have been in the past, before vaccinations, health insurance and evacuation protocols. So how did travellers in history protect their health, and what did they carry in their medical kits?

French anarchist, Alexandra David-Neel, took strychnine. Disguised as beggars, scrambling through rugged Tibetan terrain at night to avoid detection, she and her companion, Yongden, were already exhausted when moonlight broke the cover of darkness as they approached a village: “we put our loads down, drank a draught of the clear water that flowed past us, swallowed a granule of strychnine to rouse fresh energy in our tired bodies, and took the dreaded passage at a run.”

Strychnine, derived from the seeds of Strychnos nux-vomica, was a popular stimulant and remedy for heart ailments in the nineteenth century and still in use in 1924, when Alexandra made her desperate bid to enter the forbidden city of Lhasa.

In seventeenth-century Japan, the haiku poet, Matsuo Bashō, strengthened his aging legs before one of his thousand-mile walks by applying artemesia moxa (wormwood): a traditional Chinese heat treatment to free the flow of Chī or life-force.

When Isabella Bird, who suffered chronic back pain, travelled along the length of Japan from Tokyo to Hokkaido in 1878, her guide, Ito, suggested applying moxa, but Isabella declined to experiment. She had brought with her the morphine (opium)-based medicines widely available in disease-ridden Victorian England: commonly known as ‘laudanum’, they were used to treat infants and adults suffering everything from coughs and colds, to depression, diarrhoea and cholera, as well as pain. Opium was an active ingredient in a popular cough mixture that some of you may remember: Dr J. Collis Browne’s ‘Chlorodyne’ which was available over the counter well into the 1960s.

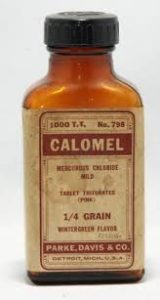

The Scottish naturalist, Mungo Park, was better equipped than most eighteenth-century travellers to survive the fevers and parasites that killed many Europeans attempting to penetrate the West African interior: he was a medical doctor. During Park’s first journey to trace the course of the River Niger, desperate with dysentery, he treated himself with high doses of calomel or mercury chloride, a common treatment before the dangers of mercury were understood: though severely damaging his mouth and throat, it proved effective.

Eight years later, Park was again in West Africa, determined to follow the River Niger to its outflow, wherever that might be. But after a year of tortuous travelling during which most of his expedition members died from disease, Park was within days of achieving his objective when he, too, perished, though not from sickness.

For travellers past and present, malaria is one of the most insidious tropical diseases. Years of chronic malaria blew up into a near-fatal attack for me when I worked in Papua New Guinea. Before new anti-malarial drugs were developed – from the 1940s – the disease had for centuries been treated with quinine. And it was quinine that Octavie Coudreau took to control repeated attacks of fever while surveying the Amazon River system in north-east Brazil during the late 1890s. Quinine did not save her husband, Henri, who died in her arms from cerebral malaria, but it enabled her to continue charting the Amazon herself for a further ten years.

One of the reasons that sixteenth-century philosopher, Michel de Montaigne, undertook his eighteen-month tour across Europe on horseback was to seek treatment for his kidney stones and chronic constipation. He drank mineral waters at health spas in Plombières in France, Baden in Germany, and La Villa in Italy, but in Rome his problem reached a crisis and he sought out a French doctor. After taking double doses of cassia and Venetian turpentine (a larch oil and strong purgative), Montaigne’s relief was dramatic. Venetian turpentine is still on the market, used these days to harden horses’ hooves. I do not recommend it as internal medicine!

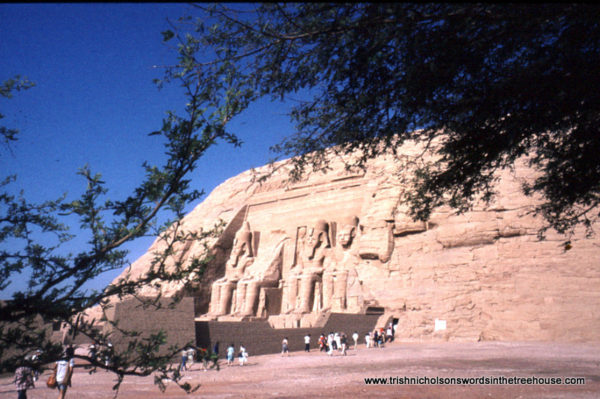

Herodotus, traveller, historian, and storyteller in the fifth century BCE, does not tell us whether he became sick on his extensive travels, but he was greatly impressed by Egypt’s physicians: “The practice of medicine is so specialised among them that each physician is a healer of one disease and no more. All the country is full of physicians, some of the eye, some of the teeth, some of what pertains to the belly, and some of internal diseases.”

In fact, the Egyptians were pretty advanced in healthy living. Your detox regime is nothing new: “For three consecutive days in every month they purge themselves, pursuing health by means of emetics and drenches; for they think that it is from the food they eat that all sicknesses come to men.”

And more than 2,000 years later, health specialists are still telling us the same message. If there is not an ‘Egyptian Diet’ being promoted somewhere, there probably should be.

For this series of posts, I have chosen specific themes, but in Passionate Travellers, I recount complete journeys of the past for you to follow step by step, and discover why these travellers undertook such difficult and dangerous adventures, often risking their lives to achieve their quest.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History

It is also available in a digital edition from Amazon or from your favourite digital book supplier.

You can read the background to Passionate Travellers and find out who they are here:

Read a review by Sam Law (@readworldbooks) on his bookblog Its Good to Read.

And another review by travel memoirist, Valerie Poore (@vallypee) on her review blog Valerie Poore’s Memoir Reviews