This is the tale of how Wilhelm and his brother Jacob came to write the fairy tales that fed our childish imaginations and that of earlier generations – their first published collection appeared in 1812: Children’ and Household Tales (Kinder-und Hausmärchen).

This is the tale of how Wilhelm and his brother Jacob came to write the fairy tales that fed our childish imaginations and that of earlier generations – their first published collection appeared in 1812: Children’ and Household Tales (Kinder-und Hausmärchen).

Once upon a time, in the German village of Hanau, there was an honest and hard-working lawyer called Philipp Wilhelm Grimm. Although not high-born, so well respected was he that the ruling aristocracy appointed him a judge.

Philipp and his wife Dorothea had nine children: one girl and eight boys, though three of their sons died in infancy as often happened in those days. Being only eight years between the youngest and eldest of the surviving Grimm children, they all enjoyed each other’s company, but Jacob and Wilhelm were special friends; they were inseparable.

Their temperaments were different and they complemented each other. Jacob, older than Wilhelm by one year, liked to know where things came from and how they worked; he always had his head in a book. Wilhelm, a delicate child, liked stories and music, and was more convivial than his brother.

And then in 1796, when Jacob, the eldest of the children, was 11-years old, their father died. The family drew even closer together to cope with this tragedy. But Dorothea was determined to give her eldest sons a good education despite their financial straits, and she knew the only way to do that was to send them away.

Jacob and Wilhelm went to live with their aunt, Henrietta Zimmer, in their mother’s home town of Kassel, where Henrietta was lady-in-waiting to the princess of Hessia-Kassel. They attended the best high school, but they were now the sons of a poor widow; there was little hope they would follow their father’s footsteps in studying law: only the elite could enter university.

For four long years the brothers worked assiduously at their studies. Jacob coached Wilhelm with his science homework; Wilhelm helped Jacob with his compositions.

In fact, they graduated at the top of their classes. Aunt Henrietta was so impressed, she asked the princess to appeal to the king on the boys’ behalf. The kind-hearted princess did so, and a special disposition allowed Jacob to enter Marburg University in 1802, Wilhelm a year later.

Jacob was lonely at first, but once Wilhelm joined him they revelled in the academic life, studying even harder as those without birthright often do, reading widely and taking an interest in everything that was going on.

And a lot was happening during that time. It was known as the Romantic Era, not because everyone fell in love, although they did in a way, as we shall see.

It all started with the French Revolution. Privileged people of the previous century had insisted upon rigid conduct, rational thought, and knowing ones place in the social order which, for most of the people, was at the bottom. But the ideals of personal liberty and equality that spawned the Revolution had cast a spell on scholars all over Europe.

In England, Samuel Coleridge and William Wordsworth wrote a collection of poems called Lyrical Ballads, which included The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and Kublai Khan; it was full of non-rational emotions and delightfully imaginative nonsense. Shelley and Byron wrote of the ecstasies and agonies of falling in love.

Meanwhile, Walter Scott was probing his roots with historical novels of heroic clan chieftains and distressed maidens. Traditions of villagers and peasants were sought after; these were the old ballads and stories – the folklore that now inspired young intellectuals with fraternity, if not actual equality.

And at their university desks, Jacob and Wilhelm listened to their professor, Friedrich Carl von Savigny, who said the essence of law could be understood only by knowing ancient customs and language. Equally spellbound, the brothers read Ludwig Tieck and the Schlegel brothers on the origins of German culture and literature when they should have been studying jurisprudence. Our heroes were not careless sons and nephews however. While they began collecting folk tales they continued their legal education, but before this was put to the test, tragedy struck once more.

Fate took the life of Dorothea Grimm, leaving orphaned her fifteen-year-old daughter, Charlotte, and three young sons still at home.

Jacob, responsible for supporting his family, worked as a librarian in Kassel where Wilhelm joined him later. Together, with the full resources of the library at their bidding, they soon added to their collection of Märchen (folk tales). By 1812, the Brothers Grimm published their first modest collection of 86 folk tales, followed by 70 more two years later. By 1818 they published two volumes of Deutsche Sagen (German Legends) – 585 of them; demonstrating scholarship that won them both honorary doctorates from their old university.

Even when Wilhelm married his childhood friend, Dortchen Wild, he and Jacob continued the same pace of work. Gathering tales was a family activity: Dortchen and the Wild family had long been a well-spring of stories, so had the Hassenpflugs, the family that Charlotte later married into, and young brother Ludwig, then studying art, painted the illustrations for their tales.

Groups of friends and neighbours gathered to pass-on stories they had heard from their nursemaids, their servants, or from aged relatives – story themes known in many forms all over Europe.

The brothers still complemented each other: Jacob focused a little more on linguistics and medieval research, while Wilhelm moulded different versions and excerpts of oral tales, or those found in the rare old books they collected, and re-fashioned them into literary form with a distinctive ‘storytelling’ style. Sometimes this meant switching plots, changing incidents, or even characters, and knitting different stories into one. Calvinist morality and patriarchy of the times underpinned the editing process, for their fairy tales, fables and legends were intended to educate as well as to entertain.

Inevitably, there is something of Wilhelm’s own nature in the stories he polished that might, for example, explain why he changed Snow White’s jealous mother into a step-mother. Is there such a thing as an original or ‘pure’ folk tale? To some degree is not each a product of every storyteller through the centuries?

And these were turbulent times. Napoleon had challenged most of Europe; German principalities fought over territory while rival factions within their borders competed for power, and everywhere, discontent bubbled-up among the workers, peasants and dispossessed youth.

The Brothers Grimm, too, had their struggles. Lack of high connections and political patronage denied Jacob the promotion he had earned at the royal library in Kassler. They both resigned at the cost of more financial difficulties.

But eventually, in the city of Göttingen, in the Kingdom of Hannover, their true value was recognised: Jacob was offered a professorship of old German literature and became head librarian; Wilhelm was appointed librarian, becoming a professor later. During these productive years, the brothers continued jointly publishing folk tales, but also pursued their specialist subjects: Jacob’s on German grammar and ancient German language and law; Wilhelm’s on old ballads and Teutonic heroic legends. They focused on their teaching and studies, unaware of another event arising from the times and about to challenge them.

Now it happened that a new king came to the throne of Hannover. His name was King Ernst August ll. Intent on crushing any ideas of liberty and equality that had wrecked the French aristocracy, this king abolished the constitution, dissolved parliament, and required all state employees to swear an oath of allegiance to his personal authority. He would wield absolute power in the land. Prominent people, afraid to lose their privileges, complained from behind their hands or in closed rooms.

Only seven brave men spoke out in protest – the Brothers Grimm among them. Forced to flee before the king’s wrath and banned from other principalities that feared the king, they returned to Kassler, finding themselves again in dire circumstances.

In life, sometimes we have to take decisions on matters of principle, or for the sake of the future, even though we seem to lose much in the present. Fate often has a way of redressing the balance.

Jacob and Wilhelm began work on the massive task of compiling a German etymological dictionary. It earned them little, but for three years they stuck at their labours in characteristic fashion.

Then another new king, in another kingdom, Frederick Wilhelm IV of Prussia, offered the Grimms research professorships at the Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Here the brothers flourished. And eight years later, when Germany, too, had its revolution – though not as bloody as that in France – both Jacob and Wilhelm were elected to the new National Assembly. But the principalities would not come together and democracy could not take root. Revolution fizzled out.

The Brothers Grimm retired from both politics and academia to focus on their other work, especially the dictionary. It was a monumental undertaking that sought to trace the origin of every German word: the first volume, published in 1854, contained 1,824 pages and that was only up to the word Biermolke.

Wilhelm died in 1859. Jacob, utterly bereft without the companion of his life, continued to work on the dictionary until his death four years later. Between them they had only reached the letter F, but later scholars built on their foundations.

And their fairy tales lived happily ever after.

Source of biographical facts: (1) http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm.html which has a full list of all the Grimm’s published works and links to electronic texts and many related sites. (2) The Complete Fairy Tales, translated and annotated by Jack Zipes (Vintage Books 2007). It includes a number of stories found among the Grimm’s correspondence not yet edited and polished by them: a useful insight into their editing process. The book also contains a list of all the people who contributed tales to the Grimm’s collection – none of whom were peasants.

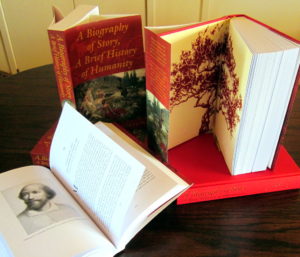

If you enjoy folk tales, legends, myths and sagas, you will love A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity. A cultural history of the power of stories from prehistory to the digital age seen through the eyes of storytellers from all over the world. “This isn’t just a book, it’s a treasure trove.”

If you enjoy folk tales, legends, myths and sagas, you will love A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity. A cultural history of the power of stories from prehistory to the digital age seen through the eyes of storytellers from all over the world. “This isn’t just a book, it’s a treasure trove.”

It is so good to see you back Trish! And thank you for a wealth of information that I certainly did not know about the Brothers Grimm. Who needs to do the housework anyway? So who cares if it was a bit long? It was as much fun to read as you say it was to write. xx

Thank you, Sue, It’s lovely to be back. Yes, this was fun to write, but surprisingly difficult in such a different style; not in finding the words, they came easy enough amid chuckles, but I found the punctuation tricky with phrasing I don’t normally use, and had to edit it two or three times. Need to write more ‘fairy tales’ obviously.

That was a fantastic post, Trish. It’s good to have you back. If I can make my blog half as interesting as your’s, I’d be over the moon! That German dictionary must be some size, take 7 dwarves to lift it. Well done Trish great stuff.

George x

Ha ha! I love your ‘seven dwarfs’ idea, George, can just picture it. Blogs are such a personal thing, they’re all different, and yours is interesting too, in rather a special way of sharing your personal discovery of Shakespeare, not everyone would have the courage to do that in this age of ‘one-up-manship’ And soon, you can tell us of your adventures in Rome with Julius Ceasar 🙂

What a lovely post, Trish – so much information about which I had no idea at all! So much work has gone into this – and it’s a delight to read. Makes me want to go back and read the fairy tales all over again. xx

Thank you Gaby, it was such fun to write, I think when that happens, the smiles somehow get into the words. I hope you find time to go back to some of the fairy tales, if it’s only reading them to the kids when they’re sick! xx

Woh! Trisha how did I miss this post? It read beautifully, I felt like I was reading a fairytale and yet it was all true. Amazing how some stories last through the centuries and never grow old.I only hope in this pc society and with the”don’t scare the children” brigade that these tales are still around for future generations.

Anne, you couldn’t have said anything I wanted to hear more. Thank you. It is all true, very carefully researched, but just for the fun of it, I wanted to mimmick the ‘fairy tale’ style of these fairy tale writers! It was huge fun, and surprisingly difficult to do. I don’t know whether it could be called ‘creative non-fiiction’, it is to me, but perhaps too trivial for the academics who create these labels. Oh I think the Grimm’s tales will survive. It’s odd people should feel so ‘threatened’ by the written word when it comes to ‘scaring the children’, when toys, video games and TV programmes for children seem to be all about killing!

You are right about violent films and video games but children can’t be taught Humpty Dumpty the nursery ryhme in case they are upself when he can’t be put back together.I don’t think children think about it too much,my children didn’t get upset. I think your story of the brothers would be a good prologue to a book of their fairy tales,I know I love reading about the author especially if they’ve lived in another century and in a land far far away….

Pingback:Blog Carnival #2: PAST MYTHS, PRESENT LEGENDS | An Aotearoa Affair

Having said I wanted to comment, it’s now taken me ages Trish! Apologies, I’ve been mega busy. I really enjoyed this – I did Children’s Literature as part of my degree last year, and the beginning of the course was all about oral tradition, fairy tales and the beginning of published literature – and how originally there was no such thing as stories specifically for children. They would have listened to the same tales round the fire as their parents did.

Over the years, as you have mentioned, these tales changed enormously depending on the social politics and fashions of the time, and the personal beliefs of the storytellers. Particularly in recent years – and even in the Grimm era – many of the ‘fairy tales’ were stringently cleaned up. The most interesting snippet about this, for me, was learning that in medieval France – where LRRHood is said to have originated – if a girl was said to have ‘seen the wolf’, it meant she had lost her virginity. Which puts a far different spin on the tale that is usually told to preschoolers these days as a subtle reminder not to wander off or talk to strangers! 🙂

Hello Alison, your comments were well worth waiting for, thank you. That is fascinating about “seeing the wolf”. These old tales open up so many more things to discover, one needs to study the society and culture where they originated and their different forms were told. One of my long-standing interests – a book that may or not be completed one of these days – is a study of storytelling in the context of major social and historical events at the time. I’m so pleased you enjoyed the post, and your comments have stirred me up again. 🙂