Pinnacle of spiritual aspirations and battle ground of cultural identity: Montserrat is a story of religion, politics, war, arts and letters – the lifeblood of Catalunya.

Pinnacle of spiritual aspirations and battle ground of cultural identity: Montserrat is a story of religion, politics, war, arts and letters – the lifeblood of Catalunya.

Long before powerful men felt entitled to own mountains, perhaps 5,000 years ago, hunters and gatherers left the caves of Montserrat where they had lived, and began to grow food on the plains below. During the day, their descendants looked up from their fields at the crazy, serrated peaks; at night they repeated around their hearths stories and legends about them handed down from their ancestors. They gave these astonishing rock formations names like La Mòmia (the mummy), La Monieta (the little mummy), and La Trompa de l’Elefant (the elephant’s trunk).

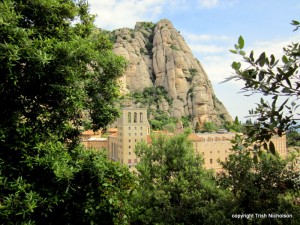

The jumble of peaks rises to 4,000 feet; some look like praying hands, others like accusing fingers. Technically, they own the ugly name of ‘conglomerate’ – pebbles, sand and clay held together in a natural cement of limestone – materials laid down when these mountains were lowlands covered in water (a long, long time ago). Easily eroded by sun, wind, rain and frost, crests were rounded and smoothed, chasms opened between them 100 metres in depth, and caves became numerous, some 500 metres deep, pillared with stalagmites and stalactites. (A note for those who can’t remember the difference: ‘tites’ come down, ‘mites’ go up).

The jumble of peaks rises to 4,000 feet; some look like praying hands, others like accusing fingers. Technically, they own the ugly name of ‘conglomerate’ – pebbles, sand and clay held together in a natural cement of limestone – materials laid down when these mountains were lowlands covered in water (a long, long time ago). Easily eroded by sun, wind, rain and frost, crests were rounded and smoothed, chasms opened between them 100 metres in depth, and caves became numerous, some 500 metres deep, pillared with stalagmites and stalactites. (A note for those who can’t remember the difference: ‘tites’ come down, ‘mites’ go up).

The earliest written records of Montserrat concern one Wilfred The Hairy, a Catalan noble whose name in that language is Guifré el Pilós. Guifré’s army drove out the Moors in 875 AD, enabling him to become the first count of Barcelona. His suzerainty included Montserrat, 30 miles to the west, but as it was already a site of pilgrimage with four hermitages, he donated it to Ripoll, the Benedictine monastery which he founded in the north of Catalunya. And so began the uneasy marriage between politics and religion that led to centuries of domestic strife.

Ripoll was too far away to bother with the hermitages until 1025 AD, when the grandson of Wilfred The Hairy, Oliba Cabreta, was elected abbot of Ripoll and sent a contingent of monks to Montserrat to establish the first Benedictine monastery at the hermitage of Santa Maria. The monastery flourished, especially after the cult of Our Lady of Montserrat began to attract donations and pilgrims from all over Europe in search of miracles – a pre-occupation of The Middle Ages.

Ripoll was too far away to bother with the hermitages until 1025 AD, when the grandson of Wilfred The Hairy, Oliba Cabreta, was elected abbot of Ripoll and sent a contingent of monks to Montserrat to establish the first Benedictine monastery at the hermitage of Santa Maria. The monastery flourished, especially after the cult of Our Lady of Montserrat began to attract donations and pilgrims from all over Europe in search of miracles – a pre-occupation of The Middle Ages.

Our Lady of Montserrat, or Moroneta (‘dark woman’), the Black Madonna is a Romanesque wooden statue of Madonna and child whose origins are cloaked in legend – carved by Saint Luke and carried to Montserrat by Saint Peter – but actually dates from the 12th century. The Madonna’s face and hands are brown: pragmatists say the varnish has darkened from age and candle smoke, but you are free to believe she was made in the likeness of the dark and beautiful woman depicted in the Song of Songs – an Old Testament story known also as the Song of Solomon, or the Canticles.

Success finally led to independence from Ripoll as well as recognition from high places. When Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue to the Americas, the Papal Legate who accompanied him was Bernard Baïl, a former monk at Montserrat. The Master printer, Johannes Luschner was brought from Germany to set up one of the earliest printing presses for the monastery’s own publishing house – Abadia de Montserrat – and a new church was consecrated in 1592. It had taken 32 years to build – hardly surprising in that terrain.

But politics and the outside world could not be denied: the spiritual importance of Montserrat and the culture of Catalunya had to survive the oppression of Ferdinand and Isabel of Spain in the 15th century; the two more centuries of turmoil and power struggles that followed; Napoleon’s sacking of the buildings in 1812; the Civil War of the 1930s – in which 23 monks lost their lives, their tombs are in the crypt of the Basilica – and further oppression during the Franco regime until its downfall in 1975.

But politics and the outside world could not be denied: the spiritual importance of Montserrat and the culture of Catalunya had to survive the oppression of Ferdinand and Isabel of Spain in the 15th century; the two more centuries of turmoil and power struggles that followed; Napoleon’s sacking of the buildings in 1812; the Civil War of the 1930s – in which 23 monks lost their lives, their tombs are in the crypt of the Basilica – and further oppression during the Franco regime until its downfall in 1975.

Franco visited Montserrat several times and usually followed the custom of kissing the hand of the Madonna. According to Michael Eaude (Catalonia: a cultural history), while Hitler met with Franco in an unsuccessful bid for German troops to pass through Spain, Heinrich Himmler, his chief of Police, made a side-trip to Montserrat in pursuit of his obsession with the Holy Grail – he probably ‘passed’ on kissing the Madonna, though.

Although Franco tried to outlaw the language, Mass at Montserrat was always said in Catalan. The iconic status of Montserrat held it in thrall to politics: during the 1960s and early1970s, it became a focus for international opposition to the regime, hosting an ‘occupation’ of artists and literary figures.

Although Franco tried to outlaw the language, Mass at Montserrat was always said in Catalan. The iconic status of Montserrat held it in thrall to politics: during the 1960s and early1970s, it became a focus for international opposition to the regime, hosting an ‘occupation’ of artists and literary figures.

Over its turbulent history, necessitating recurrent renewal and reconstruction, Montserrat became synonymous with the regeneration of Catalan language, culture and identity – the Renaixença. And it continues still.

In a quiet corner among Montserrat’s trees, a bronze statue of one of the world’s greatest cellists marks his centenary in 1976. He was a Catalan, and in Wikipaedia acrid debate as to whether he should be listed first under his Catalan birth name of Pau Casals i Defilló, or the name more familiar to the rest of the world – Pablo Casals – continues to scroll down several pages. Pau means ‘peace’ in Catalan, and he was, indeed, awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. At the invitation of his friend U Thant, he wrote the music, to words by W.H. Auden, for a ‘Hymn to the United Nations’, conducting its first performance in New York in 1971, shortly before his 95th birthday. He died two years later in Puerto Rico where his mother was born, though she was of Catalan descent.

In a quiet corner among Montserrat’s trees, a bronze statue of one of the world’s greatest cellists marks his centenary in 1976. He was a Catalan, and in Wikipaedia acrid debate as to whether he should be listed first under his Catalan birth name of Pau Casals i Defilló, or the name more familiar to the rest of the world – Pablo Casals – continues to scroll down several pages. Pau means ‘peace’ in Catalan, and he was, indeed, awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. At the invitation of his friend U Thant, he wrote the music, to words by W.H. Auden, for a ‘Hymn to the United Nations’, conducting its first performance in New York in 1971, shortly before his 95th birthday. He died two years later in Puerto Rico where his mother was born, though she was of Catalan descent.

Eighty or so monks at Montserrat continue to lead lives of spiritual growth while offering hospitality and guidance to pilgrims. Many Catalan families make annual visits at Easter or during the summer holidays; religious and cultural groups hold events and retreats, and the Barcelona Football Club give thanks there for their triumphs. If you are lucky, the traditional Catalan dance, the sardana, may be performed in the square in front of the Basilica. I saw it on a Sunday morning in front of Barcelona cathedral.

Eighty or so monks at Montserrat continue to lead lives of spiritual growth while offering hospitality and guidance to pilgrims. Many Catalan families make annual visits at Easter or during the summer holidays; religious and cultural groups hold events and retreats, and the Barcelona Football Club give thanks there for their triumphs. If you are lucky, the traditional Catalan dance, the sardana, may be performed in the square in front of the Basilica. I saw it on a Sunday morning in front of Barcelona cathedral.

Among the treasures of Montserrat is a library of a quarter of a million books and manuscripts, some extremely rare; a museum of Biblical archaeology, including Sumerian cuneiform tablets from 3,500 BC (the time and form of the tales of Gilgamesh), and a collection of original paintings, not only by Catalan artists such as Pablo Picasso and Dali, but el Greco, Monet, Degas, and Caravaggio’s Saint Jerome.

Another asset – a living treasure – is the Escolania, the boys’ choir and oldest conservatoire in the world: its earliest documented activities go back to the thirteenth century. To hear the choir sing Salve Regina, as it does every lunch time after Mass, is a high point of a visit to Montserrat that I was determined not to miss.

Another asset – a living treasure – is the Escolania, the boys’ choir and oldest conservatoire in the world: its earliest documented activities go back to the thirteenth century. To hear the choir sing Salve Regina, as it does every lunch time after Mass, is a high point of a visit to Montserrat that I was determined not to miss.

The square in front of the Basilica was crowded; queues extending the entire length of the square shuffled slowly through doors on either side of the main entrance, waiting their turn to kiss the hand of the Madonna at the back of the altar. I slipped through the main door of the Basilica, and became attached to a solid aggregate of people jammed into the back of the church, listening to the end of Mass and hoping to get into a pew to hear the choir. Being tall was an advantage: able to breathe air instead of hair, I used a well-tested method to make progress in that situation – leaning very gently into the person in front until my body heat forced them to inch forward. In this fashion I came to the back of the last pew, about hip height, but Mass was over. As people left their seats, others edged in at either end of the pew. Pressed on all sides, I could see myself trapped there.

So I confess. There was no excuse. It wasn’t panic, it was premeditated. I vaulted over the back of the pew, landing with a dull thud on the hard wooden seat. There were some sharp intakes of breath and a few mumbles, so I smiled and nodded at my nearest neighbours before focusing on the choir preparing to start. Indeed, you may be shocked, but without that little initiative, I would have been unable to bring you this photograph which you might not otherwise have seen.

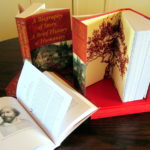

If you would like to learn more about Pau Casals, his story was written down by Albert E. Kahn, Joys and Sorrows: Pablo Casals, His Own Story (1974) Touchstone Books/Simon and Schuster. Paperback.

Trish Nicholson is the author of A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity. An entertaining cultural history of the power of stories in the comedy and tragedy of human affairs in societies past and present.

Thanking you again, Trish! Have never been to Montserrat and it has been lovely to not only visit with you, but learn some of the history as well. And then you made me giggle at the vision of you vaulting over the back of the pew and getting toffee nosed glances from those around you. Wonderful 🙂 xx

So glad to have given you a giggle, Sue. I did feel a bit embarrassed about confessing, but discovered this morning that not only has the monastery at Monserrat got a website and a Twitter account, it retweeted my post, so I feel forgiven 🙂 xx Thank you @Montserratinfo

Fascinating post, Trish. Wonderful insight into the history of an enchanting place. Great photos too:)