It was a tragic event for Bhutan when, in 2013, fire destroyed the Wangduephodrang Dzong, a fortified monastery built in 1638.

It was a tragic event for Bhutan when, in 2013, fire destroyed the Wangduephodrang Dzong, a fortified monastery built in 1638.

The King walked sadly among smouldering ruins where salvage operations had managed to save many historic treasures and holy relics. No casualties were reported, but the trauma was felt throughout the country and by Bhutanese living overseas.

Ironically, this beautiful dzong with its narrow courtyards and long, ornate wooden balconies was being renovated, the work more than half finished.

Although some have blamed traditional building materials for vulnerability to fire, the one temple that was not destroyed – Mithrub Ihlakhang – still had the original earth flooring, which had been replaced by wood in the rest of the complex. And like most of these ancient defensive structures, it was built on top of an extraordinary rock formation, on a ridge, making access difficult for fire-fighters.

Fire is an old enemy in Bhutan. The original Tashiccho Dzong in Thimphu was built in the 12th century and burned down six-hundred years later. Punakha Dzong has suffered a whole series of accidental fires in the past. Paro Dzong was destroyed by fire in 1907 and immediately re-built, and Drugyel Dzong, gutted by fire caused by an unattended butter lamp in 1951, remains a ruin at the head of the Paro valley.

Fire is an old enemy in Bhutan. The original Tashiccho Dzong in Thimphu was built in the 12th century and burned down six-hundred years later. Punakha Dzong has suffered a whole series of accidental fires in the past. Paro Dzong was destroyed by fire in 1907 and immediately re-built, and Drugyel Dzong, gutted by fire caused by an unattended butter lamp in 1951, remains a ruin at the head of the Paro valley.

Earthquakes, too, have taken their toll on dzongs throughout the country, not only in the past but most recently in 2009 and 2011.

Wangduephodrang Dzong will be rebuilt, but the question of how much modernisation should go into renovating and reconstructing dzongs is complex; it is not only an architectural issue.

Wangduephodrang Dzong will be rebuilt, but the question of how much modernisation should go into renovating and reconstructing dzongs is complex; it is not only an architectural issue.

Dzongs are more than ancient monuments; their antiquity and splendour are of more than historical and decorative importance – they are living communities of monks and administrators, surrounded by symbols of great cultural and spiritual significance. Some 300 people normally worked in Wangduephodrang Dzong; Tashiccho Dzong has, at times, housed over a thousand monks.

Although Bhutanese Buddhism goes back two thousand years, monastic orders are not archaic institutions: they are fundamental to the modern state of Bhutan.

Although Bhutanese Buddhism goes back two thousand years, monastic orders are not archaic institutions: they are fundamental to the modern state of Bhutan.

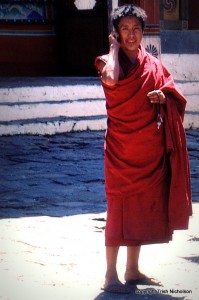

Monasteries have websites, monks use mobile phones. Monks play key roles in support of the wider society in education, health, administration and divination, as well as in spiritual guidance.

Young men may spend a year or two completing their education in a monastery before taking up careers elsewhere; others become lay monks, living within the community.

Buddhism extends from the monasteries to the street, the workplace, the home – to every facet of life and death. This is why, to many Bhutanese, the loss of Wangduephodrang Dzong is a keenly felt personal bereavement as well as a national tragedy.

“And somebody has to polish, fill and light hundreds of butter lamps in the dzong’s many temples – each flame representing Buddha’s Enlightenment and the desire to emulate his awareness. For specific days and ceremonies, thousands of tormas – tiny pyramidal shapes of flour and butter dough – are fashioned by hand to be placed along the altar with the butter lamps. Both humble tasks are acts of devotion and a form of meditation.”

Excerpt from the illustrated e-book travelogue: Journey in Bhutan: Himalayan Trek in the Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon