Humour, the most idiosyncratic of emotions, often evades the writer who tries to be funny. So what is the secret of a book that has kept us laughing for 124 years? Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) has been continuously in print since 1889 and sold millions.

Humour, the most idiosyncratic of emotions, often evades the writer who tries to be funny. So what is the secret of a book that has kept us laughing for 124 years? Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) has been continuously in print since 1889 and sold millions.

Despite its very Englishness – who else would name a dog Montmorency? – Three Men in a Boat had international influence, becoming required reading for literature in Russian school curricula. Incidentally, so were works of Charles Dickens – while visiting Moscow in the 1970s, I was bemused to receive many expressions of sympathy, for what were believed to be the impoverished conditions in England, as my hosts plied me with extra helpings of borshch.

The funny thing about humour is that critics don’t like it: early reviews lambasted Three Men in a Boat. True, at times it reads like an elaborate pub crawl from Kingston-Upon-Thames to Oxford, and long, witty asides swamp the original intention of an informative travel guide to London’s great river, but what exasperated the critics was its appeal to the ‘lower classes’, which, in retrospect, and considering the massive sales figures, appears to include us all. The gulf between literary judgement and reader enjoyment was never so great.

Over the next twenty years, Jerome’s other books and plays were not always treated kindly either, leading him to quip in his autobiography that he was “the best abused author in England.”

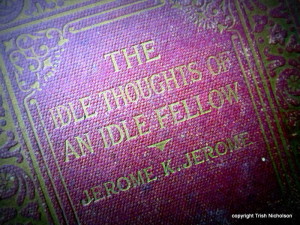

Perhaps it was hard for the literati to accept meteoric popularity for this 30-year-old ‘unknown’ living in London’s East End – a contemporary of the equally undiscovered J. M. Barrie and George Bernard Shaw. Having had essays, satires and short stories rejected, Jerome had only two earlier books published: On the Stage – and Off (1885), a comic novel based on his brief and impecunious career as an actor – stage name Harold Crichton – during which he claimed to have played “every part in Hamlet except Ophelia,” and a collection of amusing essays The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow (1886). But after Three Men in a Boat, he was able to give up his day job as a solicitor’s clerk and write full-time, producing over twenty novels and collections, and nine plays.

Humour is still not taken seriously enough. If you follow short story writing competitions, you may have noticed that humorous tales – however engaging the story, or well written – are rarely placed: misery and horror seem preferred. It would be a pity to be deterred by this. Of all aids, survival of the human condition most requires laughter and optimism. Jerome was well aware of this: his father’s business collapse left the family in the grip of debt collectors, and by the time he was 15 years old he was orphaned, required to earn his own living. So how has Jerome managed to regale us for over a century?

Impossible though it is to do justice to his humour by writing about it, The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow provides us with some clues. In the essay On Babies, Jerome describes infants as: “Odd little people! They are the unconscious comedians of the world’s great stage… Each one, a small but determined opposition to the order of things in general, is for ever doing the wrong thing, at the wrong time, in the wrong place, and in the wrong way.”

Incongruity – opposition to the order of things – provides humour by placing a normal action or remark in the wrong context and, in Jerome’s style, in an understated way. He never says: ‘A funny thing happened….’ He shows us a developing situation as if he had no prior knowledge of the consequences; when they emerge we recognise the funny side for ourselves.

His style is droll and straight-faced – he does not laugh at his own humour. On the first day of their boating trip, he observes, with mild surprise, that Harris, one of his two companions who is supposed to be rowing, suddenly flings himself on his back, kicking his legs in the air. Only then does Jerome realise that, while musing at length on the passing landscape, Harris forgot he was steering, and they “got mixed up a good deal with the tow-path.”

Jerome frequently uses self mockery, and embarrassing truths we can all relate to. Returning to On Babies, after describing the hazards of misidentifying a swaddled baby’s gender when pressed to make some suitably admiring comment on the “bald-headed dab of humanity”, he advises: “If you desire to drain to the dregs the fullest cup of scorn and hatred that a fellow human creature can pour out for you, let a young mother hear you call dear baby “it”. Your best plan is to address the article as “little angel.”

He also exaggerates and applies irreverent images: when well-dressed young ladies are induced to ride in their boat on the Thames, although the men make a show of dusting the seat beforehand, the ladies deem conditions unsatisfactory to their fabrics with the fidgeting “as of early Christian martyrs trying to make themselves comfortable against the stake.”

As a writer of satire, irony produced Jerome’s deepest humour. In a more flippant aside in Three Men in a Boat: “There is an iron ‘scold’s bridle’ in Walton Church. They used these things in ancient days for curbing women’s tongues. They have given up the attempt now. I suppose iron was getting scarce, and nothing else would be strong enough.”

And in an extended political assault in his short story The New Utopia which begins: “I had spent an extremely interesting evening. I had dined with some very “advanced” friends of mine at the “National Socialist Club”. We had had an excellent dinner: the pheasant, stuffed with truffles, was a poem; and when I say that the ’49 Chateau Lafitte was worth the price we had to pay for it, I do not see what more I can add in its favour.

After dinner, and over the cigars (I must say they do know how to stock good cigars at the National Socialist Club), we had a very instructive discussion about the coming equality of man and the nationalisation of capital.”

The story describes a vision of society in which equality is taken to extremes: everyone has the same colour hair; identical clothing and numbers instead of names do away with gender differences; babies are reared from birth by the State, and “THE MAJORITY” is always right. And this was long before Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and forty-five years before George Orwell’s 1984.

Although Three Men in a Boat is a novel, history and geography are imaginatively and accurately portrayed. Jerome knew the area well: the previous year, he and his new bride Ettie spent their honeymoon on the Thames. The book is still used as a travel guide by those wishing to follow the author’s footsteps; most of the pubs Jerome, Harry and George sampled are still there, and you can view their route along the river via Google.

Shared here are only a few pointers I found in Jerome’s writing; if you want to write humour, I suggest you read him, and other authors, closely to discover their techniques for yourself. Technique, though, is only part of the story: style, word choices, author ‘voice’ and pacing all play significant roles and you will need to develop your own. But a caveat: writers can get carried away with ‘being funny’ to the extent of compromising authenticity, particularly in non-fiction genre. In travelogue, for example, integrity is essential to a professional reputation as a travel writer rather than a comedian.

[Sources: I have my own venerable, cherished copy of The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow – results of an addiction to book dust – but most of Jerome K. Jerome’s works are available as free downloads in various formats from Project Gutenberg, including Three Men in a Boat, and his autobiography My Life and Times].

Trish Nicholson is a social anthropologist and the author of A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity – the global history of storytelling, an interwoven plot of history and literature.

Great post, Trish. And I so agree about reading funny writing to inform one’s own.

I think there’s a difference between wit (individual lines, or characters who are funny) and situational humour. Neither are easy – the funniest scene I’ve ever read is the dinner party in Larry’s Party by Carol Shields – that made me laugh out loud. But for great wit, I think I’d go back to Dickens to find a real master.

Thanks, Jo. Yes, it’s a large and complex subject, but interesting because humour is so individualistic. One person’s smile is another’s guffaw, so by reading widely we can find the writers that most appeal to each of us.