Our folk tales have survived for millennia. ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ was told 5,000 years ago*, its moral wisdom more than ever relevant today.

My last blog post revealed true facts from around the same period in an ancient Irish myth, but some stories are much, much older, commemorating dramatic discoveries by our foraging ancestors.

One of the first great turning points for humanity was learning how to make and control fire. Archaeologists have found evidence of cooking around a communal fire in Qesem Cave (Palestine) dated to 300,000 years ago, and it is likely that human groups in many places knew how to use, and even to make fire, thousands of years earlier. Fire transformed their lives.

“Fire kept them warm and dry during cold, wet seasons. They could now cook their food. Previously indigestible but easily available tubers and other mature vegetation could be eaten when cooked, and the spoils of their hunting roasted, increasing variety and protein in their diet. Fires kept at bay the wild beasts that preyed on them at night, and even deterred pesky insects whose buzzing and biting drove people crazy on warm damp evenings and sometimes made them sick.

In time, they learned to use fire to flush out game when hunting; burn off dead grasses to encourage new growth; subdue the bees to raid their honey and to fell a tree by burning around its base. They even discovered how to carry smouldering embers with them to new campsites to save the arduous task of making new fire.

Perhaps most important for Story, they had warmth and light at their command and a safe focal point for social gatherings. Light during the long evenings extended their active hours, enabled them to mend their traps and nets, weave new carrying slings, perhaps turn a hollow reed into a flute – and share stories and songs around the fire.”

They had witnessed wild fire as a terrifying mystery, a raging, engulfing inferno that brought instant death to all living things, and yet, after the rains, they had seen the gradual rebirth of vegetation.

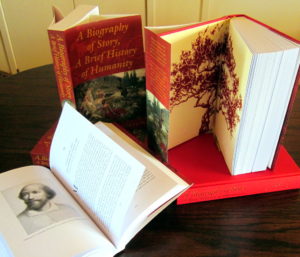

“The man or woman in each band who produced fire doubtless became a local hero, perhaps even a great leader or revered storyteller. How often they must have told their tale…” (Quoted passages from A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity.)

A landmark in human culture, the domestic hearth has ever since been to us a symbol of life, renewal and conviviality. In ancient Greece it served as the family altar, the focus of offerings and prayers for the longevity of the householder’s lineage. In ancient Rome, the eternal flame in the temple of the goddess Vesta (in Greek, Hestea) – the guardian angel of humanity – was tended by her priestesses, the Vestal Virgins.

The practice continued until Theodosius the Great converted to Christianity in AD 380 and extinguished the sacred flame (re-lit, after a fashion, by Swan Vestas household matches in the 19th century). And in many cultures around the world, fire still conjures the power to purify, initiate and ritually transform.

The best-known myth of fire’s origin is probably that of the Greek Titan, Prometheus. Instructed by Eros to complete the earth by creating Man, Prometheus fashions humans out of clay, and is so pleased with the results that he wants to give them a unique gift enjoyed by no other creature. He decides the gift should be fire. A rash choice because fire was a privilege exclusive to the gods – it was not his to give.

Under cover of darkness, Prometheus steals a lighted brand from the gods’ fire and gives it to humanity. When fires are lit all over the earth, however, Jupiter sees their glow from the heights of Mount Olympus. He tracks down the thief and inflicts upon Prometheus a terrible punishment.

Most stories about how humans first acquired fire involve risk, bravery, or clever tricks. Although we cannot date them precisely, the folk tales of indigenous societies seem to me emotionally closer to what that first experience of making fire must have felt like and they are probably much older. The brave hero is more often from humble origins, and they commonly reveal cultural knowledge about making fire, for example, naming a tree that provides the best wood for drilling a spark or for carrying glowing embers.

In A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, I relate a traditional tale of the Tse-Shaht, First Nation peoples of Canada.

“The fierce and terrible Wolf People were the only ones to have fire and they guarded it jealously. Young Ah-tush-mit, who loved to dance and sing, was not taken seriously by his people, but the Chief supported his request to attempt to steal the fire because the strongest, bravest and wisest men of the tribe had already tried and failed … But Ah-tush-mit kept a secret which he told no one.”

Ah-tush-mit, Son of Deer, beguiles the Wolf People with his dancing until they invite him into their company, where he dances closer and closer to their hearth until, to the Wolf People’s amusement, he leaps right over the flames and his knees begin to burn. Ah-tush-mit escapes through the door and runs away as fast as he can.

His secret? He had tucked dry, resinous sticks of spruce inside his cedar-bark knee bands. The sticks caught fire and set the cedar bark smouldering until Ah-tush-mit reached his home and the jubilant villagers fanned them into flames.

For the Sanema-Yanomami forest-dwellers in Venezuela, only Irawami the caiman possesses fire which he keeps shut up in his mouth behind huge sharp teeth. But the humans and the other animals make a plan together to steal it. They hold a party for everyone and invite Irawami. The animals perform all kinds of hilarious tricks until Irawami cannot stop himself from laughing. Quick as a flash, the humming bird darts into his mouth and takes in his beak a ball of fire, placing it in the heart of the sacred Puloi tree – the tree the Sanema-Yanomami use to make fire.

In myriad ways, Story commemorates our greatest moments of fear, joy, and wonder. For all our sophisticated science and technology, these remain our paramount emotions. Though details and context may change, we still need the stories that made us human in the dawn of our pre-history. “Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire.” (Gustav Mahler).

*Dr Jamie Tehrani and Sara Graça da Silva in Royal Society of Open Science journals: 3(1) January 2016.

******

Dr Trish Nicholson is the author of A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, the first global social history of storytelling which you can read about here, where there are also links to the Introduction and the Table of Contents.

Dr Trish Nicholson is the author of A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, the first global social history of storytelling which you can read about here, where there are also links to the Introduction and the Table of Contents.

In the UK, the book is available from bookshops or you can claim a 25% discount direct from the publisher here. From anywhere else in the world, The Book Depository will supply the book free of any freight charge.