Straw sandals, fold-away boats, a penny-farthing bicycle, camels, yaks, ponies, even a cow: just a few of the means by which my ‘passionate travellers’ made their incredible journeys across vast distances.

Straw sandals, fold-away boats, a penny-farthing bicycle, camels, yaks, ponies, even a cow: just a few of the means by which my ‘passionate travellers’ made their incredible journeys across vast distances.

We are a migratory species. For millennia, our ancestors walked across continents and land bridges to every habitable place on the planet; we have walked far longer than we have used any form of transport.

The Buddhist monk, Fâxiân, strode some 10,000 miles across Central Asia and India in the fourth century; Matsuo Bashō tramped in his straw sandals for thousands of miles around Japan meditating on his haiku poetry in the sixteenth century; and in 1925, Alexandra David-Neel tramped across the Tibetan Plateau disguised as a beggar to enter the forbidden city of Lhasa. Trekking in high places is still popular with travellers. If you have a yen to do so, you can trek beside me in Bhutan.

Gonçalo da Silveira, sixteenth century Jesuit martyr, would love to have stalked across what is now Zimbabwe alongside his Shona guides who maintained a relentless pace for hours on end, but he was sick with fever. Like most Portuguese travellers he was carried in a litter – a covered hammock. It was early December and the rivers were swelling with rain, too deep to wade. “As he could not swim, Gonçalo had to squeeze himself into a large earthenware jar normally use to store grain, and be pushed and tugged through swirling currents, only his white knuckles visible as he gripped the rim and prayed for merciful deliverance.” (Passionate Travellers)

Second in longevity to walking is water transport. Long before animals were domesticated and wheeled carts invented, our forebears all over the world found ways to follow rivers and cross seas whether on floating logs, rafts of tree bark or bundled reeds, in dugout canoes, or in animal skins stretched over willow or bamboo frames. The speed and distance capability of later boats increased once sails were devised – at least 6,000 ago.

Of the twenty-one unique journeys related in Passionate Travellers, seventeen involved sea or river transport at some point, in vessels ranging from camel-skin coracles to luxury liners. In the mid-fifth century BCE, Herodotus sailed in a Greek merchant ship from Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum in Turkey) to the port he called Heracleion and the Egyptians called Thonis, and then travelled some 600 miles up the Nile to Elephantine (near modern Aswan) in a barge that had to be towed from the bank to overcome the contrary current.

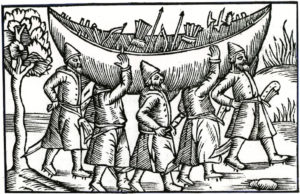

During his wanderings in Persia (Iran), Herodotus learned of collapsible, portable boats made of camel skin stretched around wooden frames. They were made in Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea. Similar ‘folding boats’ appear in ancient Norse sagas. In the Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson relates that Skídbladnir was ‘the best of ships’; capable of holding the Aesir and their arms, but able to be folded and carried between water ways. The way myth and history interlace has always fascinated me (see A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity); Skídbladnir is described in fantastical terms in the Edda, but these boats were not mythical fancies.

When the diplomat, ibn Fadlān, journeyed from Baghdad to the shores of the Volga River in the tenth century, his party rode in similar contraptions to cross the many rivers draining from the Ural Mountains into the Caspian Sea: “We had boats made out of camel skin, to allow us to pass the rivers we needed to cross in the land of the Turks.” And two centuries later, the wooden, Rūs trading vessel in which the Abbot Daniel travelled from Kiev to Constantinople (Istanbul), while not ‘collapsible’, was built light enough for the crew to carry it around deadly cataracts on the Dnieper River.

When the diplomat, ibn Fadlān, journeyed from Baghdad to the shores of the Volga River in the tenth century, his party rode in similar contraptions to cross the many rivers draining from the Ural Mountains into the Caspian Sea: “We had boats made out of camel skin, to allow us to pass the rivers we needed to cross in the land of the Turks.” And two centuries later, the wooden, Rūs trading vessel in which the Abbot Daniel travelled from Kiev to Constantinople (Istanbul), while not ‘collapsible’, was built light enough for the crew to carry it around deadly cataracts on the Dnieper River.

In the sixteenth century, even in the best ship afloat at the time – the Portuguese four-masted carrack designed for stability as well as speed – long-distance sea travel was hazardous. The Jesuit martyr, Gonçalo da Silveira, warned that: “The voyage from Portugal to India can only be related, or even believed, by him who has had that experience.” Drenched and thrown around in storms, food corrupted by decay, drinking water brackish, sickness and death among the crew were routine. A third of crews regularly perished – rigging systems were adjustable to enable fewer men to handle the ship on its return voyage.

As to seasickness, you might like to try the remedy recommended by the crew of the clipper on which Ida Pfeiffer sailed from Copenhagen to Iceland in 1845: “hot-water gruel with wine and sugar” followed by “small pieces of raw bacon highly peppered.”

It worked for Ida.

Robert Louis Stevenson claimed to be the only person on board his hired yacht, Casco, who ate dinner during forty hours of dipping and lurching in heavy seas on their approach to the Marquesas Islands. Even Ah Fu, the Chinese cook, rushed, heaving, back to the galley after serving the meal. In the absence of witnesses, we must accept the Storyteller’s word … or not.

By the time the artist, Marianne North, sailed to Australia for one of her flower-painting expeditions, steam technology had turned international sea travel into a luxury experience – for those who could afford a first class berth. “For exercise, if the weather on deck was too boisterous, Marianne could walk the long salon where chandeliers flashed shards of light between gilded mirrors on either side, endlessly repeating the comforting glow of polished mahogany and plush furnishings. She could immerse herself for hours in a deep-buttoned leather armchair beside a fire in the library feeling quite at home. And in a sumptuous dining room twinkling with polished silver on snowdrift table cloths, she could be amused by the wit and intellect of her own kind, with the added honour of occasional invitations to the Captain’s table.” (Passionate Travellers)

Perhaps the oddest means of transport was Tom Stevens’ penny-farthing or ‘high-wheeler’ bicycle, then a relatively new ‘boys’ toy’ in America. The Boston-based Pope Manufacturing Company had imported the first high-wheelers from England in 1878, and went into production a year later. Tom, an English immigrant, acquired a ‘Columbia Ordinary’ with a 50-inch front wheel that came up to his shoulder. The Columbia was built for speed: there had been fatalities. But Tom was impatient for fame and fortune. With the jauntiness of the innocent – he had learned to ride only the week before –Tom wheeled across North America from San Francisco to Boston, and then cycled around the world; the first person to achieve either feat.

For these short blog posts, I have chosen specific themes of interest to travellers, but in Passionate Travellers, I recount complete journeys, unique adventures with sketch-maps of routes for you to follow step by step, and discover why these travellers undertook such difficult and dangerous challenges, often risking their lives to achieve their quest.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History.

You can read the background to Passionate Travellers and discover who they are here:

Read a review by Sam Law (@readworldbooks) on his book-blog Its Good to Read.

And a review by travel memoirist Valerie Poore (@vallypee) at Val Poore’s Memoir Reviews