As we tuck a packet of nuts and raisins, a chewy bar or a handful of dried fruit into our pocket before a journey, we follow an ancient tradition of travellers. But they had more need of it than most of us.

As we tuck a packet of nuts and raisins, a chewy bar or a handful of dried fruit into our pocket before a journey, we follow an ancient tradition of travellers. But they had more need of it than most of us.

When the Buddhist monk, Fâxiân, left northern China in 399 CE, to walk across Central Asia to India, he was pretty sure to find a monastery for food and a bed each night for the first couple of thousand miles along the Silk Roads, until he reached Kutcha (Kuqa), an oasis on the edge of the Tarim Basin. From there, he and two companions had to cross the infamous “desert of death” – the Taklamakan. “There is not a bird to be seen in the air above, nor an animal on the ground below. Though you look all round most earnestly to find where you can cross, you know not where to make your choice, the only mark and indication being the dry bones of the dead.” (A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms, translated by James Legge.)

The desert crossing took them “a month and five days”, and it was as well that Fâxiân was an ascetic, accustomed to long fasting; they could have eaten only what they could carry with them: chewy roasted grains, nuts, dried fruits, perhaps an initial supply of rice cakes bound with honey or butter. Food was wrapped into little parcels of cloth ‘water-proofed’ with fat or wax, or in twists of paper, but it would have been impossible to keep desert sand out entirely and brings to mind gritty egg sandwiches on family beach picnics.

When Fâxiân and his companions trekked south through high mountain ranges (which took at least another two months), they found many monasteries, but in between, yak herders could offer small quantities of barley grain, milk, butter, and yak cheese. I discovered yak cheese – chugo – while visiting yak herders at their high summer pastures in Bhutan. The cheese is cut into small cubes and hung inside the herders’ tents for several months to be dried and smoked over the cooking fire, until hard and greyish-yellow in colour. Never mind that in your mouth it feels like a lump cut from the heel of your hiking boots: it is easy to carry and provides hours of nutritious chewing on a long high-altitude trek. (In the photograph below, taken inside a yak herder’s tent, chugo is hanging near the fire on the left.)

Because Alexandra David-Neel and her lama-companion, Yongden, travelled as fugitives across the Tibetan Plateau, they had to carry their own food: bricks of black tea, and a wrap of rancid butter to make their morning ‘butter tea’; barley flour to moisten and roll into a mouth-sized ball (tsampa); and some small scraps of dried beef for the daily ‘soup’, seasoned with wild onions when they found some – the local Tibetan diet. On one occasion they ran out of food: trapped in a hut by snowdrifts for over a week, they were reduced to boiling an old strip of pig skin that Yongden kept for greasing the soles of his boots.

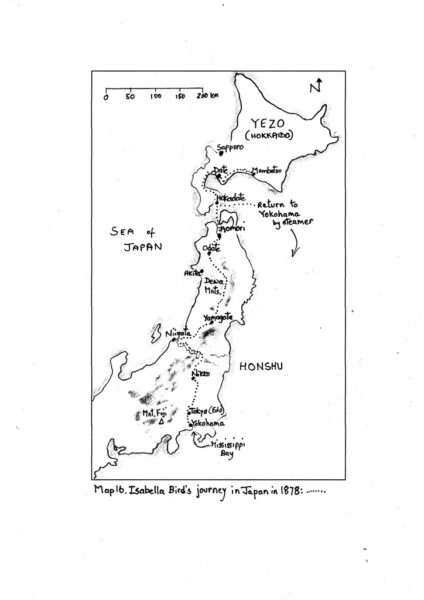

During her eighteen-month journey along the length of Japan, Isabella Bird had packed “beef lozenges” and bought a supply of cucumbers en route to supplement the diet offered in local inns where “the rice was only partially cleaned, the eggs had seen better days, and the tea was musty.” Unfortunately, her beef lozenges grew mould after her baggage was caught in unexpected floods, and rats ate her cucumbers and gnawed her boots while she slept.

During her eighteen-month journey along the length of Japan, Isabella Bird had packed “beef lozenges” and bought a supply of cucumbers en route to supplement the diet offered in local inns where “the rice was only partially cleaned, the eggs had seen better days, and the tea was musty.” Unfortunately, her beef lozenges grew mould after her baggage was caught in unexpected floods, and rats ate her cucumbers and gnawed her boots while she slept.

Some travellers had other reasons for carrying their own food. Ida Pfeiffer’s nineteenth-century-bourgeois horror of “uncleanliness” obliged her, during her journey in Iceland, to refuse food from any peasant’s kitchen. Instead, she kept rye bread and cheese in her bag to nibble in private.

In Gladys Aylward’s case, it was lack of money. By 1932, when she crossed Russia on the Tran-Siberian Railway, peasants peddled vatrushka, shashlik, pickled cucumbers, and glasses of black tea from steaming samovars at station stops. But Gladys had packed a spirit stove, kettle, and small pan along with tea, coffee essence, tinned food and biscuits to sustain her for the journey: while other passengers swarmed to the hot-food stalls, Gladys squatted on the platform heating baked beans for her lunch.

I relate more closely to the times and places past travellers journeyed through by searching for the small intimate details of their experience. And for these short blog posts, I have chosen specific themes that most serious travellers cope with, but in Passionate Travellers, I recount complete journeys of the past for you to follow step by step, and discover why these travellers undertook such difficult and dangerous adventures, often risking their lives to achieve their quest.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History Released on 28 April, and you can order here.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History Released on 28 April, and you can order here.

You can read about the background to Passionate Travellers and discover who they are here:

And read a review by Sam Law (@readworldbooks) on his book blog It’s Good to Read