By the time I’d written Passionate Travellers, I’d read more than a hundred travel accounts going back more than 2,000 years – that is the time span of the book – and a recurrent question in my mind was: where did they get the money for these incredible journeys to the ends of the earth.

By the time I’d written Passionate Travellers, I’d read more than a hundred travel accounts going back more than 2,000 years – that is the time span of the book – and a recurrent question in my mind was: where did they get the money for these incredible journeys to the ends of the earth.

Travelling was a slow process: people could be ‘on the road’ for months, even years, and most of my ‘passionate travellers’ were not rich – they were ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Yet they had to hire transport, pay for levies, taxes and safe passes, buy food and, sometimes, offer bribes.

For Shakespeare, financial security and ready cash were a prerequisite for travellers:

“Crowns in my purse I have, and goods at home,

And so am come abroad to see the world.”

But Paulo Coelho has a point when he claims that “Travel is never a matter of money but of courage.” So how did these courageous travellers sustain themselves?

One was a mendicant ascetic, surviving on offerings from devotees: the fourth-century Buddhist monk, Fâxiân, travelled for fifteen years to achieve his quest. He walked from Xi’an in northern China, along the Silk Roads through Central Asia, across the deadly Taklamakan Desert to the Himalayas, and crossed India before returning by sea – and surviving a shipwreck – to Quingzhou (on the Shandong Peninsular). A donor paid for his boat fare. That giving alms is one of the five ways to achieve Nirvana has enabled many Buddhist pilgrims to travel the world.

Other religions supported their followers too. To prepare for their intended pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the Mongolian monk Rabban Sauma and his pupil, Marko, launched a fund-raising appeal in the large Nestorian Christian community in Khanbalik (Beijing). Church elders thought them mad to attempt such a journey but were eventually persuaded to help.

Kublai Khan would have added to these funds: apart from the fact that his mother was a Nestorian, he looked upon Rabban Sauma as an unofficial ambassador for his Mongol Empire. The Khan issued the pair with a p’ai-tzu, a safe pass requiring Mongol-controlled territories along their route to render assistance. But there were schisms within his vast empire: the two travellers barely escaped with their lives.

And in 1901, British missionary, Mildred Cable, was sponsored by the China Christian Mission Society (CCMS) to work at Huozhou in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion in northern China. Twenty years later, travelling and preaching up and down the Silk Road and crisscrossing the Gobi Desert on a high-wheeled mule cart, Mildred and her companions raised enough money for their daily food by selling copies of the gospels.

But not all missionaries received official support. Gladys Aylward’s dedication was tested more than most. She had been rejected by the CCMS on account of her limited education. Undaunted, though struggling in the 1930s depression, Gladys eventually saved enough from her maid’s wages to buy a £47.10s ticket for the Trans-Siberian Railway that was supposed to connect her all the way to Tientsin in China.

She left London with only a few coins in her pocket, and a £2 Thomas Cook travellers’ cheque hidden in an old corset in her battered suitcase. Even so, it was not a lack of money that disrupted her travel plans but finding herself caught up in an undeclared war and being arrested by Stalin’s secret police.

Access to funds was a major problem for most women travellers in the past. Ida Pfeiffer was in her forties by the time she had raised two sons on her own, and saved enough to make her first overseas trip – from her Vienna home to the Middle East. Even then, she had to obtain permission from male relatives to publish an account of her travels. But that first book was popular: the royalties paid for her next journey, to Iceland and Norway, her income supplemented by collecting natural specimens and selling them to museums. Ida always had to travel on a tight budget, but with these sources of income, she journeyed twice around the world during the remaining twelve years of her life, collecting some 2,000 specimens each time.

Isabella Bird, too, was held back by family commitments and was in her late-forties when she made her first long, solo journey from Scotland. In 1878, she boarded a steamship bound for Yokohama. During the next eighteen months, Isabella travelled the length of Japan on the backs of tough little Japanese ponies, and an occasional cow, and crossed the Tsugaru Straits to Yezo (Hokkaido) where she visited communities of indigenous Ainu. Like Ida Pfeiffer, Isabella published accounts of her journeys, the proceeds paying for further travel. But neither were ‘travel writers’ in the sense of choosing a location in order to write about it: for both women, publishing their travelogues was simply the best way to pay for their next trip.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the illustrated lecture tour was a popular entertainment, especially in America. After Thomas Stevens cycled from San Francisco to Boston on a penny-farthing or high-wheeler, in 1884, he continued to cycle around the world the following year. Magazine articles and lectures to enthralled audiences brought him fame and sponsorship for further travel in Africa, India, and Russia.

And Annie Smith Peck gave lectures on the ‘new science of archaeology’ to raise funds and gather sponsorships for her mountaineering exploits. In Peru, in 1908, she climbed the north peak of Mount Huascarán (21,812 feet), setting the record for the highest altitude then attained by any climber in the Americas: the peak was later renamed Cumbre Aña Peck.

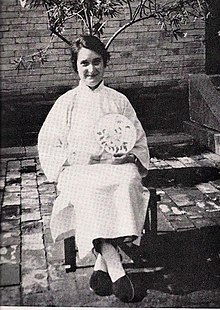

Perhaps the most intriguing funding arrangements were those of the French anarchist, opera singer and orientalist, Alexandra David-Neel. She had given up her singing career by the time she married her cousin, Philip, in Tangiers in 1902. She left him almost immediately to continue studying Buddhism in France, returning only to arrange her travel to India for a nineteen-month study tour with financial help from her long-suffering husband abandoned at home.

In the event, the ‘tour’ became a fourteen-year trek through China and Central Asia to Tibet, concluding with Alexandra’s illegal entry into Lhasa disguised as a beggar. It is unclear exactly how much Philip paid towards Alexandra’s activities – she did have some funds of her own – but he undoubtedly acted as her agent throughout her travels, even successfully forwarding money to her in a China tearing itself apart with civil war.

Ardent travellers found ways to indulge their passion, even though it was often more difficult for women. As another of my ‘passionate travellers’, American journalist and world traveller, Harriet Chalmers Adams, wrote in 1910: “If a woman be fond of travel, if she has love of the strange, the mysterious and the lost, there is nothing that will keep her at home.”

For this series of posts, I have chosen specific themes that most serious travellers cope with, but in Passionate Travellers, I recount complete journeys of the past for you to follow step by step with the help of rough sketch-maps of each route, and to discover why these travellers undertook such difficult and dangerous adventures, often risking their lives to achieve their quest.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History in print and digital editions.

You can read the background to the book on my book page here:

And read reviews by Its Good to Read reviewer, Sam Law (@readworldbooks) here: and by travel memoirist Valerie Poor (@vallypee) here.