(Pic: Shutterstock)

Leeches are a common hazard for passionate travellers. But would anyone actually want leeches?

Well yes, the ancient health remedy of applying leeches to the body is still a recognised medical practice, though now targeted more scientifically and called ‘hirudotherapy’. Leeches are used to withdraw small amounts of blood over an extended period to relieve localised inflammation and to help restore circulation – after cosmetic surgery for example. A leech’s saliva secretes an anti-clotting agent and, compassionately, a topical anaesthetic, so patients don’t feel its three sets of shark-sharp teeth sinking into the tip of their noses or puncturing their piles.

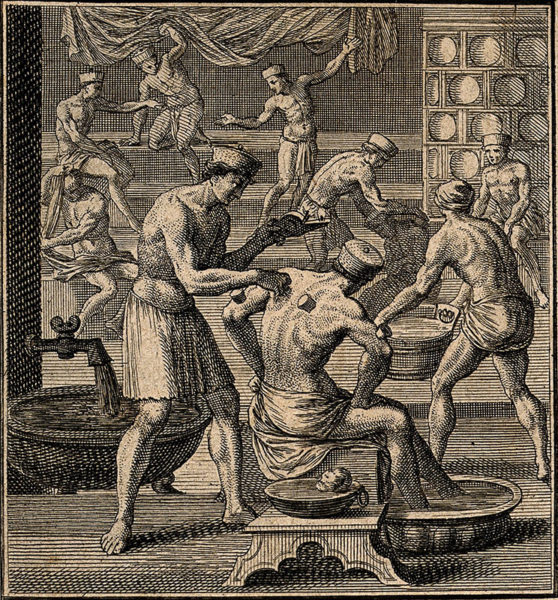

In the past, the cause of most sickness was believed to be either ‘too much’ blood or ‘tainted’ blood which had to be removed. If leeches did not bring relief, doctors resorted to ‘cupping’ or hijama, a much more drastic method: they made several cuts into the flesh with a scalpel, and pressed over each wound pre-heated inverted glass cups creating enough suction to draw out large quantities of blood. The practice was popular with people taking ‘the cure’ at Europe’s health spas.

(Wellcome Library)

One of the reasons why the essayist, Michel de Montaigne, undertook an eighteen-month tour through Germany and Italy was to seek treatment for his chronic kidney stones and constipation. When he arrived at the hot-spring resort of Plombières, it was still busy with German and French clients enjoying the unusually warm autumn of 1580. The normal regime here – for which patrons were expected to stay one month – was not to drink the waters, but to undergo purging before immersion in the communal baths two or three times a day, accompanied by cupping. Montaigne observed that: “the bath at times looked as if filled with blood rather than mineral waters.”

He wisely skipped the bloody aspects of the cure, only bathing on alternate days and drinking about eight small glasses of the spring water each morning; and at the end of his ten-day stay he passed a couple of kidney stones. Montaigne recounts, with eye-stinging detail, further treatments he received at spas in Baden and at La Villa, north of Florence, in Italy.

In 1890, another ‘passionate traveller’, a doctor as well as an eminent writer, Anton Chekhov, took careful note of local medical practices during his 6,000-mile journey across Siberia to Sakhalin Island: “There are no hospitals and no doctors. The only people to treat the sick are medical orderlies. Blood letting with leeches and cupping there are, in huge brutal quantities.” He was horrified to find, by the roadside, a patient suffering from liver cancer, so exhausted that “he could scarcely breathe”, yet the district nurse had applied twelve huge blood-sucking leeches. [“Mania Sakhalinosa”, John Coope]

And how to detach the leeches you don’t want? I discovered this in Papua New Guinea. I was walking behind my three sturdy male companions in steep mountain jungle, the dense thick-leaved undergrowth slapping our legs like wet towels as we scrabbled to find a way through, when a distress call – a lusty obscenity – came from the front. Our leader (a non-smoker) wanted the cigarette I had just lit, “quick”. Then they all wanted a turn: their legs were covered in slimy leeches – “the slug-like bodies rapidly darkening and swelling with blood.” Applying a lighted cigarette to the nether end is the best way to make a leech withdraw: if it is pulled off, its mouth could remain under the skin to fester. “The cigarette was carefully handed back to me, but I no longer fancied smoking it.” [Inside the Crocodile]

The nineteenth century French explorer, Octavie Coudreau, had similar experiences while penetrating Amazon forest to survey the interior; and she would have used the same remedy because she, too, was a smoker. But leeches were the least of her problems. “Cutting back the prolific vegetation that overhung the river bank disturbed mosquitoes, ticks, chigoes (a skin-burrowing flea) and fire ants. ‘The ants fall in legions, a couple of seconds is enough for us to be covered from head to foot, and they sting eyes, ears, neck, they attach themselves to the roots of your hair … your body is swollen to the point of real pain.”’ [Passionate Travellers]

There is one other method to remove leeches. When the Victorian artist, Marianne North, travelled in Sarawak, Borneo, she was often accompanied by a British soldier employed by Charles Brooke, the popular ‘white rajah’ who then ruled the territory. Since the ‘natives’ were friendly and helpful, the only useful service the soldier performed was flourishing his sword to slice leeches from Marianne’s legs.

Even if you have one at hand, I would not recommend wielding a sword, or a machete: apart from the likelihood of leaving a bit of leech in your flesh, your aim may not be quite accurate in the slime of the moment. Do not scorn the presence of a smoker; they have their uses.

For this series of light-hearted posts, I have chosen specific themes that most serious travellers cope with, but in Passionate Travellers, I recount complete journeys of the past for you to share step by step, and find out why these travellers undertook such difficult and dangerous adventures, often risking their lives to achieve their quest.

Passionate Travellers: Around the World on 21 Incredible Journeys in History is available from Book Depository here

and from all major booksellers worldwide.

You can read why I wrote it and find out who the travellers are here:

And read Sam Law’s review on his book-blog It’s Good to Read.