These hand-painted Buddhist wall hangings are never signed. The identity of the painter is not important: it is an act of reverence and meditation.

These hand-painted Buddhist wall hangings are never signed. The identity of the painter is not important: it is an act of reverence and meditation.

This is the thangka I brought back from Bhutan: Padmasambhava seated on lotus blossoms. Shown here as the Precious Teacher, in his left hand he holds a skull cup, in his right, a vajra – the thunderbolt symbol of Tantric Buddhism. On the staff, balanced in the crook of his arm, a vase contains the nectar of life, and at the top, flames symbolise divine wisdom that destroys ignorance.

Padmasambhava is easy to recognise because he is always painted wearing the same hat, usually with the lappets turned up as they are here

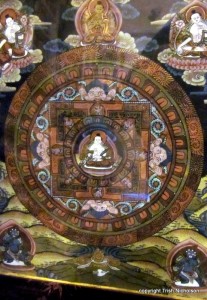

Other thangkas depict Buddha, revered Lamas, scenes from Buddhist mythology, or mandalas – geometric designs illustrating religious ideas of the cosmos and the interrelatedness of all beings. Although images follow strict rules laid down by tradition, painting a thangka requires great artistic skill and deep religious understanding. Most monks learn the art as part of their religious training in Buddhist iconography, but only the most adept specialise in painting.

Thangkas are everywhere in Bhutan – in homes, shops and hotels as well as in public buildings and monasteries – and usually accompanied by the evocative aroma of burning Juniper, symbol of life and health. Thangkas are not merely decorative but are used for instruction, for meditation, and to invoke the deities they represent.

Thangkas are everywhere in Bhutan – in homes, shops and hotels as well as in public buildings and monasteries – and usually accompanied by the evocative aroma of burning Juniper, symbol of life and health. Thangkas are not merely decorative but are used for instruction, for meditation, and to invoke the deities they represent.

Usually applied to a base of cotton, sometimes silk, the paints are derived from plants and minerals – ground up rock and sediments – using ancient knowledge and techniques.

Rocks, weathered, compressed, veined or otherwise created by geological forces over eons, produce different colours with varying properties to stay ‘true’ when used. Herbal extracts are added as natural glues and ‘fixers’ to make a water-soluble and workable consistency and a durable pigment. Monasteries have thangkas that are centuries old and still vivid.

Painted thangkas are often small, about 20 cm (8 inches) wide, and few are wider than 45 – 60 cm because that is a common width of hand-looms on which the cotton base is woven. But when images are appliquéd and embroidered onto silk panels, the thangkas can be huge. These are the thondrols – silk wall hangings that can entirely cover the courtyard wall of a dzong (a fortified monastery) and may be more than 30 metres wide.

Thondrols are displayed during the tsechu – the Buddhist festivals held each year on an auspicious date in dzongs and monasteries all over Bhutan. The deities witness the dances of tsechu and bless those who perform and attend.

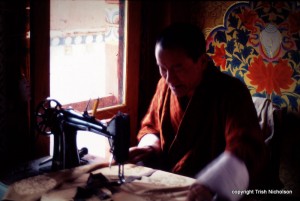

At Tashichhodzong, in Thimphu, I was fortunate to see about fifty monks working on a thondrol; because they were a bit behind schedule they worked at a feverish pace. The thondrol covered the floor of the Tshogdu – the huge chamber in the dzong where the National Assembly meets when in session.

At Tashichhodzong, in Thimphu, I was fortunate to see about fifty monks working on a thondrol; because they were a bit behind schedule they worked at a feverish pace. The thondrol covered the floor of the Tshogdu – the huge chamber in the dzong where the National Assembly meets when in session.

The Lama supervising the work allowed me to take photographs. The light was dim – monks who were hand-sewing sat by the windows – but you get the impression of the frenetic activity that was taking place.

“One monk holds a pencil drawing of a bird, transferring the design onto fabric by pricking the outline with a needle, then rubbing fine powder into the prick marks which leave a trace on the fabric beneath.

“One monk holds a pencil drawing of a bird, transferring the design onto fabric by pricking the outline with a needle, then rubbing fine powder into the prick marks which leave a trace on the fabric beneath.

Others are embroidering motifs on pieces of silk with the deft delicacy of Victorian ladies. Two large sections are being carefully sewn together by another group, and in a corner, a plump, middle-aged monk, his face nearly as red as his robes, races a treadle sewing machine as if his life depends on it. It rattles and whirrs without pause, his eyes focused on the needle, the tip of his tongue protruding between his lips in concentration.”

Excerpt from the illustrated e-book travelogue: Journey in Bhutan: Himalayan Trek in the Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon.

The photos are lovely Trish, and the info was so interesting.

Great to see you Denyse, thanks for your lovely comments on the post, glad you enjoyed it.