This post is linked from the main post for A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity

Pasted below is the introductory section to Story’s ‘biography’. (Unfortunately, I do not have here the beautiful Aldine type that we chose for the book.)

Before we meet Story

This is a true story. It is our own story told through the tales of storytellers from many parts of the world. Some of the tales you may know, others, perhaps not.

As a storywriter and a social anthropologist, I have drawn on both of these passions to create a ‘biography’ of Story that is factually accurate yet presented with imagination. Starting from the emergence of language and going through to the digital revolution, each chapter is constructed around a significant era of human history and considers the questions: Who were the storytellers? What events did they live through and respond to? How did these events affect the nature of Story? And how did Story influence events?

To achieve this interweaving of history and literature I found some remarkable storytellers to be our escorts. They include peasants and poets, playwrights and novelists and the creators of short stories: the daughters, sons, lovers and protégés of Story. Framed by an outline of history, the storytellers reveal a more personal experience of the age in which they lived with extracts from their epics, verses, tales, fables, or sagas and with anecdotes from their lives. Through their eyes we see the development and purpose of stories and better understand Story’s mission.

Stories are universal and there is a good reason for that: narrative is the mode in which our species thinks. It seems that our brains have evolved to sense the world in stories. As research uncovers more complex language skills and tool use among non-human primates and other animals, these are no longer the defining features of being human – but the storytelling brain is. As far as we know, no other creature tells stories.

The development of words would have been a long process. Stories had to wait even longer, for syntax and sentences, before they could explain past and present experience, pass on ideas, help to plan the future and, eventually, draw on symbolic thought to talk about non-physical things. We cannot know exactly when any of these events happened. But storytelling probably developed at least 300,000 years ago, when there is evidence of controlled fire used by fairly large groups of cave-dwellers, indicating an increasingly complex social organisation. These earliest findings at Qesem Cave, near the present settlement of Rosh Ha’ayin near the Israel–Palestine border, were first reported in April 2014 in the Journal of Archaeological Science and will doubtless generate much discussion; in particular, the conclusion that evidence of controlled fire use could push current estimates of human cultural activity back to much earlier dates. In this continuous and accumulative thread of humanity, it is conceivable that elements of these early experiences and the stories they generated linger as archetypes in the depths of our psyche.

Because Story emanates from our nature, it is necessary to set her biography in the context of human development, but I want to avoid any suggestion of linear progression in storytelling. This is not an evolution of literature; not an attempt to characterise early or indigenous stories as in any sense ‘less’ than later ones. Once we had cognitive and vocal capacity sufficient for storytelling, these skills set in motion change, diversity, mixing and sharing across cultures, times and places and, above all, accumulation: it is a continuing process. We know that by 5000 BC fables, myths, epics, and domestic tales already co-habited orally. These were among the first to be given permanence by early writing systems, but they were already an inheritance from many thousands of years of storytelling.

The simplicity of the most meagre tale can be deceptive and is of no less value than any other. Every narrative detail and structure is a product of its time, place and culture, but all perform Story’s roles within their context. Seeing through the eyes of storytellers as far as possible will, I hope, achieve this sense of complex interweaving and diversity over time rather than any concept of progress towards a notional literary Valhalla. Oral traditions are not only something from the past; story performance is still with us, fulfilling our insatiable desire for revelation, insight, meaning, identity, connection, wisdom and entertainment – all the gifts of Story. With this caution about Story’s timelessness, her agelessness, this book is an attempt at her ‘biography’.

The necessity, at times, to make reasoned use of conjecture is a familiar feature of biography where data may be missing for certain periods, and when biographers attempt to access a subject’s inner world by imaginative but judicious inference. Obviously, there is no documentary evidence of oral storytelling before the invention of writing, although some of the earliest written stories so far found – incised on clay tablets around 2700 BC – were certainly derived from oral tales which were much older. Nonetheless, it seemed worth including some idea of the very beginnings of storytelling, and I have approached this through traditional stories of indigenous foraging and hunting peoples who developed their cultures and tales in a similar physical environment and faced the same issues as our early ancestors.

For later periods, documentary evidence of all kinds is so abundant as to be almost overwhelming. Not only in terms of stories themselves, but also for the social and historical detail on which biographers must rely to grasp the essence of both their subjects and the ages in which they lived. That is challenge enough for a single life. To venture a biography of ‘Story’ as a conceptualised ‘character’, an omniscient presence with multiple personalities, whose life extends almost the entire length of human history, may be regarded by many as foolhardy.

Because of Story’s longevity, the tough question arose as to how to select events, stories and storytellers to convey the quality of each age, the role that Story played, and the ways in which she was affected. For this I established a few criteria. I chose as background those developments that had great impact on society at a particular point in history and which most readers would know about – though perhaps only as vague school-time memories – and within that context, focused on events of greatest significance for Story: the invention of writing, the great migrations, the age of exploration, invention of the printing press, mass education and so on through to the digital revolution. The stories and storytellers are a combination of those that are widely known and those that may be less so and, in particular, players that were especially influential (such as the fourteenth-century storyteller Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote in the vernacular for the first time in England, broadening access to stories and the ideas they contain, and the nineteenth-century scholar Peary Chand Mitra, who did the same in Bengal). And because Story is universal, I have, as far as possible, included stories and storytellers from all corners of the world. A casting vote went to those who brought with them humorous anecdotes.

Story’s manifold forms are evident in the words we enlist to describe them: tale, yarn, fairy tale, folk-tale, legend, myth, fable, parable, anecdote, short story, short fiction, vignette, saga, narrative, chronicle, and epic. While we can all recognise, in a general sense, the nuances implied by each term, whole books have been written to define ‘myth’, differentiate ‘folk-tale’ from legend and prescribe what is, and is not, ‘a short story’. And of course, stories also inhabit poems, novels, drama and films. It seems a western obsession to cut things up and label them: a process of reduction and categorisation that leads to claims of territorial rights over certain forms and demands rules of compliance. Received wisdom assures us that the ‘proper’ short story began only in the nineteenth century.

Such linear, reductionist thinking denies the whole spirit of Story and obscures her full significance in the human epic. I have freed Story from these restraints and allowed her to blossom in all her depth and wholeness. Where it matters, distinctions in this account between, for example, legend and myth, fable and anecdote or epic and novel are revealed more in their roles within a cultural and historical context than in a theoretical framework. Some readers may be disappointed by the lack of attention to definitions, but classification is not my purpose; instead, I have sat in Story’s parlour listening while she spins yarns and weaves tales. This is not a work of literary criticism: it is a celebration of the ‘life’ of Story with all its rich ambiguities and mysteries.

In these pages I hope you will enjoy finding old ‘friends’ as well as meeting interesting strangers and discovering new ways to know Story because A Biography of Story is intended, like all tales, to challenge as well as to entertain. And you might well ask, in view of all the difficulties outlined above – Why did I do it? The answer is simple: as a lover of Story, I wanted to read a book about her entire life. I found none, so I wrote one myself. Interweaving into a single narrative topics that are usually separated was not an easy task, but the entire process has been an incredible journey of discovery during which I often lost my way, coming upon treasure in unlikely places or tunnelling through mountains of the mundane to reach the unexpected, sometimes half-drowning in deep waters and, occasionally, waking from exhausted sleep to find that what I was searching for was under my pillow all along.

What kept me going was an irrepressible desire to share with you my wanderings through time and place in the company of Story. Inevitably, the saga of humanity contains tragedy as well as comedy and we are left with challenging questions about our future, but we found a lot of fun in our wanderings.

_____

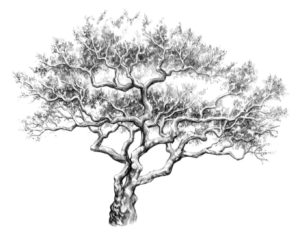

And as a reward for reading so far, here is one of the original monochrome watercolours that I commissioned from the talented illustrator, Graeme Neil Reid, and which we chose for the printed endpapers of the hardback edition.

The gorgeous acacia tree – symbol of life, of stories, of ideas, of our diverse human family – is a truly ancient species whose multiple benefits have nurtured humans since our origins. Acacia is native to Africa and Australia where some of the oldest indigenous stories to ensure our survival were told – and they still are, if we choose to listen.

A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity is published in the UK on 28th March 2017 in paperback (£14.99) and hardback (£24.99) ISBN 9781785899492 (paperback) 9781785899508 (hardback) 480 pp, illustrated.

Available in the UK, from your local bookshop; or direct from the publishers here; or from Amazon UK here.

From elsewhere in the world you can order from The Book Depository here with no freight charge.