Remember Twitter before the ‘selfie’ craze? No one bothers to read tweets without images now. Even fewer will recall computing with DOS before Windows raised our expectations to click on a picture to open a Pandora’s Box.

Our experience is increasing visual as well as virtual. But a browse through a second-hand bookshop reminds us that illustrations have always been important to literature and not only in children’s books. William Caxton (c.1422–1491), who set up the first printing press in England, made extensive use of wood-block engravings to illustrate his books.

History, biography and fiction as well as travel and cook books all have a long past of including artwork and photographs. So do newspapers: the first colour newspaper in Britain was the Illustrated London News first published in 1844.

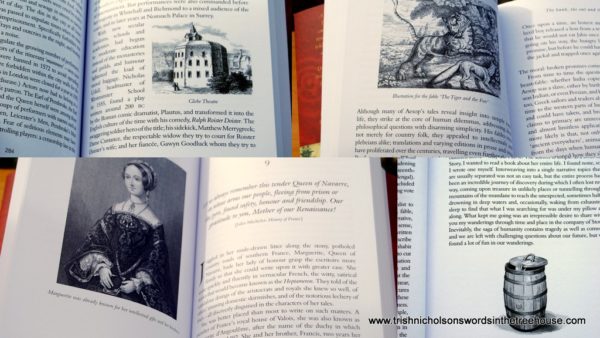

Charles Dickens’ novels kept four illustrators busy: F. W. Pailthorpe, Phiz, George Cruickshank, and John Leech, a prolific cartoonist for Punch magazine. And many of Walter Scott’s novels were illustrated.

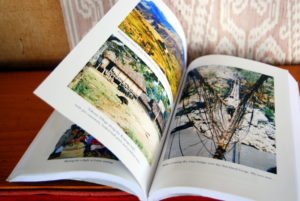

One of the benefits of digital publishing is that ebooks can be illustrated easily and cheaply; a fact that has promoted graphic novels and modern comics. Readers of digital travel books expect authors to be generous with their photographs; the ebook travelogue, Journey in Bhutan: Himalayan Trek in the Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon, contains twenty-six original colour plates.

But print books continue to hold the lion’s share of the book trade and look set to increase that, even though to include illustrations in print books still requires critical and sometimes expensive decisions.

Neither black and white nor, especially, colour images are shown to advantage on standard 80gsm paper commonly used for text in digital Print-on-Demand printing: they are better on photographic quality paper that gives clearer definition. As costs are higher for both the paper and the colour printing, authors often have to restrict the amount of artwork they include and to prioritise.

Except for cookery books, colour-printed pages are usually gathered together at one or more places in the book in groups of four double-sided pages (i.e. eight pages in all), as we did for Inside the Crocodile: The Papua New Guinea Journals.

Eight is a ‘magic’ number for printers. The reason is that books are printed on large sheets of paper holding thirty-two printed pages on each side – sixty-four book-pages per sheet – which is folded, cut and trimmed to produce sets of eight double-sided pages. Multiples of ‘eight’ are then bound together to make up the entire book – somehow, they all end up in the right order!

This is why illustrations on photographic paper are in separate sets of eight pages, and why some books have two or three blank sheets at the end: their text did not entirely fill the last set of eight.

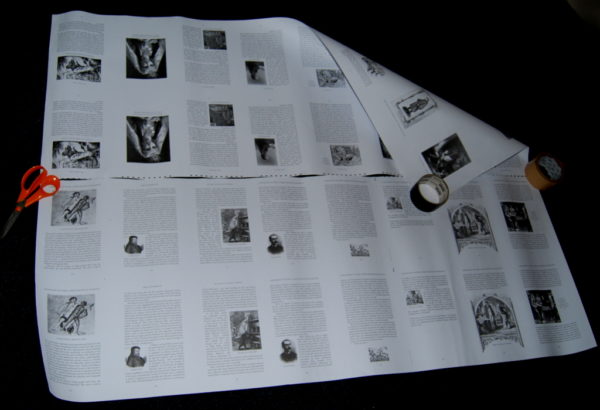

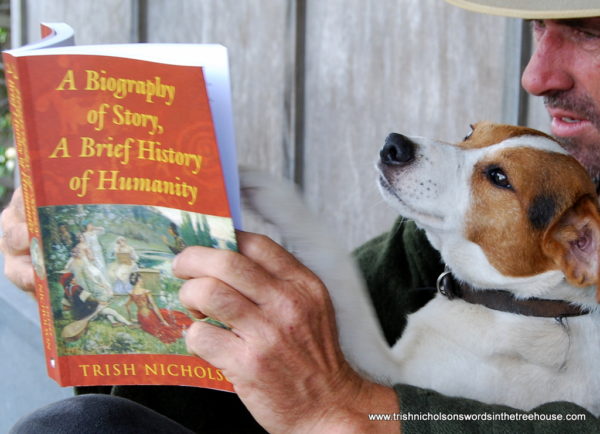

Below is one of the proof sheets sent to me for A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, to check the printing quality of illustrations (I had cut the full sheet in half to make it more manageable, so two halves are laid side by side here on the floor).

The complications for printing ‘Story’ were two-fold. Although the 50 illustrations were all in black and white, many of them were reproductions of old photographs or engravings which needed care and the best possible conditions to print clearly. In addition, I wanted them distributed evenly throughout the book, placed at relevant places in the text rather than gathered together in one or two places.

To achieve the quality we wanted, it was therefore necessary to use 100 gsm paper for the whole book. It is seductive, caressable paper, but this choice led to another complication: the heavier paper is unsuitable for standard digital printing machines. As a result, Story is printed more traditionally, with the offset lithographic process which, in any case, tends to give a finer result for illustrations than digital printing.

There was certainly no problem in reproducing the gorgeous monochrome watercolour drawings commissioned from Graeme Neil Reid, such as the little barrel at the head of this post, and below is Graeme’s vision of Ah-tush-mit Son of Deer, the folk hero of the Tse Shaht peoples of western Canada who first brought fire to the tribe.

‘Young Ah-tush-mit, who loved to dance and sing, was not taken seriously by his people, but the Chief supported his request to attempt to steal the fire because the strongest, bravest and wisest men of the tribe had already tried and failed. But Ah-tush-mit kept a secret which he told no one…’

‘Young Ah-tush-mit, who loved to dance and sing, was not taken seriously by his people, but the Chief supported his request to attempt to steal the fire because the strongest, bravest and wisest men of the tribe had already tried and failed. But Ah-tush-mit kept a secret which he told no one…’

You will find Ah-tush-mit’s secret and the rest of his story on page 19 of A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity.

Tips on sourcing illustrations:

- To engage an illustrator for your book, make contact with the artist as early as possible: good artists are in demand and have full schedules. A friend who writes children’s books had to wait for two years until the illustrator of her choice was available for new work.

- Be clear on the terms of the commissioning contract: generally, the fee for illustrations is for the artwork to be completed; it does not mean that you own the original artwork, or the copyright to it. If available, these are costed separately. You don’t need either to use the illustrations in a book and in promotional materials, but you do need publishing rights and you will have to negotiate the price of these.

- If using your own photographs they must be higher resolution for print books than for digital books – at least 300×300 dpi (i.e. density of pixels) and some may need to be higher. Talk to your printer.

- Old books can be a good source of illustrations, but beware that even though a book is out of copyright, its illustrator’s copyright could still be in force or have been re-registered. Always check thoroughly.

- Online image suppliers are numerous but check licensing fees and conditions. Costs can vary according to the type of book, print run, and size and placing of the picture you want to use. Free images from these sites are generally at too low a resolution for printing.

- Useful sites where good quality, free images that are out of copyright can often be found with careful searching are Wikimedia, Internet Archive, and Public Domain Review (art, science and literary images, with links to other open collections).

- Keep records of where you source images, and even if they are out of copyright, always credit the original artist or photographer.

If you are interested in book publication, you might like two recent posts in this series: Anatomy of a Book Cover, and How to Write a Book Blurb. And you can find much more information on choosing publishing options and printing methods, including a 7-page glossary of publishing and printing terms in, Writing Your Nonfiction Book: the complete guide to becoming an author.

Interesting post! ☺ Although it doesn’t always have what I need, I often use Pixabay for general images to illustrate articles etc. All pictures are completely free of any reuse restriction or fee.

Thanks for that tip, Alison. Images are needed for all sorts of different publications, of course, not only books.