Being Manx by birth and heritage, I saluted ‘Themselves’, the ‘Little People’ or the Faery Folk of the Isle of Man, for their benevolence during this journey – my first return to the island in thirty years. And Manannan Beg Mac y Lir, the great Celtic Sea God, for withholding his cloak of fog with which he famously deterred a visit by Queen Elizabeth ll.

Being Manx by birth and heritage, I saluted ‘Themselves’, the ‘Little People’ or the Faery Folk of the Isle of Man, for their benevolence during this journey – my first return to the island in thirty years. And Manannan Beg Mac y Lir, the great Celtic Sea God, for withholding his cloak of fog with which he famously deterred a visit by Queen Elizabeth ll.

Though a Christian island since the fifth or sixth century, Manx independence has surely been protected by Manannan. The Manx parliament, Tynwald (from the Norse Tingvollr), was inaugurated in 979 by the Vikings as an annual gathering where new laws were read out and legal cases tested. Procedures often critical to the plot of Norse sagas explored in A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, the book I was touring with.

Tynwald endures through its elected officials, the House of Keys, as an uninterrupted democratic institution 1038 years later. Its origins celebrated on the ancient terraced mound, Tynwald Hill, at St John’s each year on July 5 (Old Midsummer Day), when any Manxman still has the right to petition for justice.

And it might surprise some that although the island’s residents are British citizens, and they accept the ceremonial role of a governor appointed by the Crown, the island is not part of the United Kingdom, nor a member of the European Union. Independence and strength of spirit reflected in the Manx motto, Quocunque Jeceris Stabit (‘Whichever way you throw me, I will stand’), symbolised by the stability of the ‘three legs’ emblem.

And it might surprise some that although the island’s residents are British citizens, and they accept the ceremonial role of a governor appointed by the Crown, the island is not part of the United Kingdom, nor a member of the European Union. Independence and strength of spirit reflected in the Manx motto, Quocunque Jeceris Stabit (‘Whichever way you throw me, I will stand’), symbolised by the stability of the ‘three legs’ emblem.

Equally independent and admirably active, the island’s University of the Third Age (U3A) hosted my talk on July 4 – the last event of my book tour and final presentation of Story-power: Why We Need it to Survive.

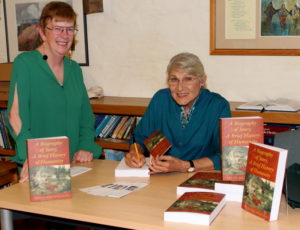

U3A embraces a wide range of interests and among my varied audience were history buffs, ardent readers, writers and a professional storyteller. A lively question time and chats over cream scones and tea after my talk still allowed time for signing copies of A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity.

Bridge Books of Port Erin and Ramsey supplied the books; for me a delightful serendipity because the owner of this independent bookshop, Harry Pickard, is the namesake and grandson of our music teacher at Castletown High School many years ago.

During a lesson on rhythm, I was the only pupil to claim I knew how to dance a polka. An exaggeration I regretted when Harry Pickard called me out to the front of the class to demonstrate the steps with him. An unintended lesson in humility I have never forgotten. And the fourth generation of the family now attends the same school.

Such continuity of culture and inheritance drew me back into the past. Despite new developments, the island’s cultural core, its values and creative accomplishments in music, craft and literature, remain dynamic. In the landscape, many carved standing stone and ancient keills – tiny stone chambers for early Christian worship – still remain. So does Castle Rushen in Castletown, its foundations dating from c. 1190.

One of my ancestors, John Stevenson, Speaker of the House of Keys, was imprisoned there in 1719 after leading a revolt against the tyranny of the Earls of Derby, the Stanley family of Knowsley, Lancashire, who had ruled as Lords of Mann since 1405.

I lived in this medieval castle, too, though thankfully not as a prisoner. I travelled on the wonderful old steam railway to return there, and chose the day that Paul, the friendly station master, recommended as promising the best weather. He was absolutely right. Thank you, Paul.

So, how did I come to live in Castle Rushen?

So, how did I come to live in Castle Rushen?

When my father was custodian, our accommodation was a flat built into the ramparts. In my teens I sprinted up the spiral staircase for the daily winding-up of the one-handed clock in the castle tower. Traditionally claimed to be a gift from Queen Elizabeth l and dated 1597 on the clock face. I climbed the steps at a more sedate pace this time, to see again the clock’s inner mechanism.

Across the lane from the castle I stopped for a pub lunch at the cheery Tap Room, where the kitchen is operated as an independent enterprise by Steve Hesketh, and relished his superb minestrone soup while I continued reminiscing.

Across the lane from the castle I stopped for a pub lunch at the cheery Tap Room, where the kitchen is operated as an independent enterprise by Steve Hesketh, and relished his superb minestrone soup while I continued reminiscing.

During our time in the castle, there had been a small museum of motley objects, and when the film crew of the BBC television series ‘Stranger Than Fiction’ came to the island, they chose to feature an early Victorian tricycle from the collection. But the presenter, the redoubtable Huw Wheldon, first had to fix a perished tyre to its rim with Cellotape! (Look closely, you can see the roll in his hand.)

And of course, as a stage-struck teenager, I got into the act to demonstrate for the cameras. Sadly, no TV contract ensued.

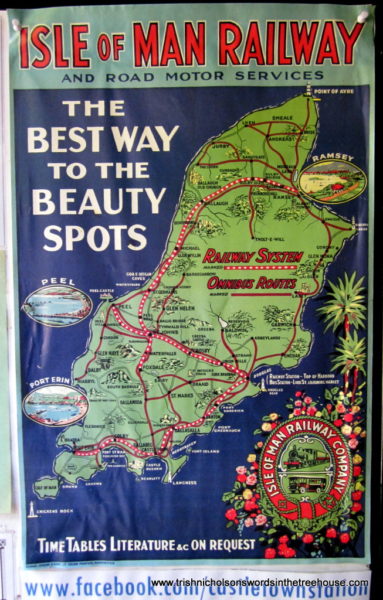

The steam train wound its way back along a dramatic, story-filled coastline to Douglas, the island’s capital, where I was staying at the Eidelweiss, a comfortable and friendly guest house overlooking Queen’s Promenade.

Queen’s Promenade is at one end of the majestic two-mile sweep of Douglas bay; the town centre is at the other – a perfect excuse, if one were needed, to travel on a traditional ‘toast-rack’ horse-drawn tram to my next nostalgic encounter.

Ned, who understands the character of each of his charges, allowed me to sit at the front with him.

Horse-drawn trams have plied the promenade, meeting passengers off the steamer on Douglas pier since 1876. Many were double-deckers as in this old postcard from around 1920.

Photo credit Ian. F. Finlay

My mission was to visit St Matthew’s church on North Quay. An emotional reconnection with the past which also solved a family mystery: why had my grandfather, Rev. Hugh Selwyn Taggart (‘Parson Taggart’) been in big trouble with his bishop?

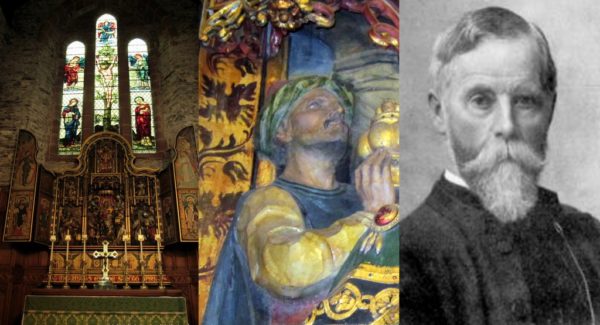

Austere, even gaunt, on the outside, St Matthew’s church interior is elegantly handsome with the work of architect John Loughborough Pearson and a stained glass window by William Morris among other notable artists. I appreciated it more now than in my childhood, when I endured many cold Sunday mornings hungry for lunch and willing the sermon to end.

Austere, even gaunt, on the outside, St Matthew’s church interior is elegantly handsome with the work of architect John Loughborough Pearson and a stained glass window by William Morris among other notable artists. I appreciated it more now than in my childhood, when I endured many cold Sunday mornings hungry for lunch and willing the sermon to end.

The ‘new’ church was built from 1895 during the time of my great-grandfather, Canon Thomas Arthur Taggart, who became its first vicar and served the parish for 31 years. He is still commemorated and there is a tradition that one of the figures in the Reredos created in his memory was based on his own features. From the pictures of both below, what do you think?

St Matthew’s was the first free parish church in the area, built to serve the local fisher-folk, street traders and other occupants of tenements along the quay. It was common at the time for churches all over Britain to charge for the hire of their high-sided, lockable, wooden pews; wealthy families rented multiple pews, reducing access to poorer parishioners. Social elevation gained recognition by an invitation to a superior pew – I’m sure Jane Austen wove this fact into a novel somewhere.

A free parish church was therefore a welcome innovation. The descriptions in church publications of my great-grandfather as a “much-loved and hard-working priest” gives a glimpse of how difficult it could be to change social attitudes. Upon his retirement, his friend, the eminent Manx artist Archibald Knox, honoured him with an illumination of his initials for the official dedication.

Thomas Arthur’s retirement marked the completion of a long and adventurous career which began as a missionary in the wilds of Kansas in America’s pioneering days – but that’s another story.

My grandfather followed his father as vicar of St Matthew’s from 1909 and further independence of spirit followed.

The bishop was appalled when my grandfather began to celebrate Mass wearing a chasuble. A garment considered too ‘high church’ and which had not been worn on the island since the Reformation – 500 years earlier. Though challenged in the ecclesiastical court, my grandfather and his congregation won their case to continue worship in the English Catholic tradition of their parish.

While he explained this history to me, Father Duncan Whitworth, the present vicar, kindly showed me that first chasuble and a photograph of my grandfather wearing it.

At least no one could accuse Granddad of wanton extravagance in acquiring this richly embroidered robe: it was hand-made by my grandmother, cut out from her wedding dress.

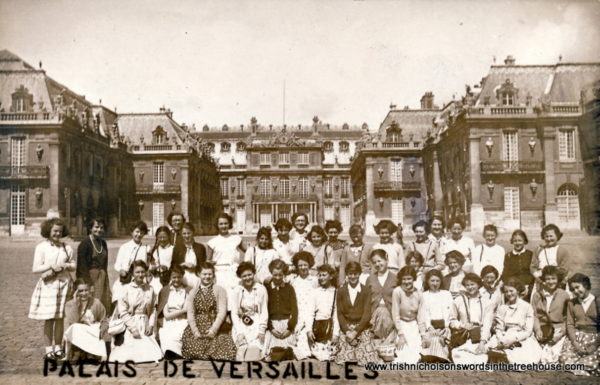

I have no family left on the island now, but on my last evening I enjoyed the company of five old chums, most of whom I had heard nothing of since our schooldays marked by a memorable class visit to Paris.

Yours truly in front row, ninth from the left.

We caught up on so many years of news as best we could. None had been able to join my talk the previous day, but when someone picked up my own much-thumbed working copy of A Biography of Story, it fell open to the tale of Senchan Torpeist, the Ollamh or Chief Bard of all Ireland, who took his followers on a circuit to the Isle of Man in the fourth century. As their boat beached, they came upon Ua Dulsaine’s lost daughter, a Druidic poet in her own right, shipwrecked during her own visit to the island and left the sole survivor.

And so, like a Celtic knot, the loop closes.

And so, like a Celtic knot, the loop closes.

You can find the full text and readings of my talk about the power of Story here

My post about the book tour events in England here

And further details of the new social history of storytelling, A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity here

For more information on the many delights and adventures waiting for you in the Isle of Man, (Ellan Vannin in Manx Gaelic) you could start with the official website. and if your special interest is history, see Manx National Heritage. And Google ‘Manx Legends’ to be presented with a hundred thousand results.

What a lovely piece – and fancy living in Castle Rushen! My mother loved the island, having stayed at the Fort Anne hotel with my father in her youth, and both retired there in the 70s. To me, it has always been a wonderfully magical place, not just because of its history but also its landscape. We used to visit for holidays and I think I’ve been to every single one of the glens. We loved the emptiness of the beaches on the west coast, too, and even the fog, through which we once drove (with an almost empty tank) on our way back from Ramsey to Braddan, where my parents lived.

What a lovely response! I can well understand why your parents loved the island and decided to retire there. The amazing thing is that there are lots of things to do and see whatever age people are, and it is so compact – notwithstanding the fog. I think this creates the strong community feeling that is very evident. My problem writing the post was keeping it short enough for a blog – so many thoughts and memories bubbled up all the time. I only had a few days unfortunately, and it is such a long, long way from New Zealand. Thank you for your contribution. Trish

You’re most welcome. The piece brought back memories.

What fascinating stories of your family history–and how intriguing to live in a castle. I would love to hear the rest of your ancestor’s adventures and wonder how you know them so well–did he leave a diary, or letters, as well as being a well-known personage in society?

Hello Chris, glad you enjoyed the post. There are a few letters, photographs and other documents and old newspaper clippings, but also a booklet my Auntie Betty wrote a long time ago about their childhood as well as family stories, but I haven’t delved into them in any great detail. As you know, family history is something you never quite get to the end of.