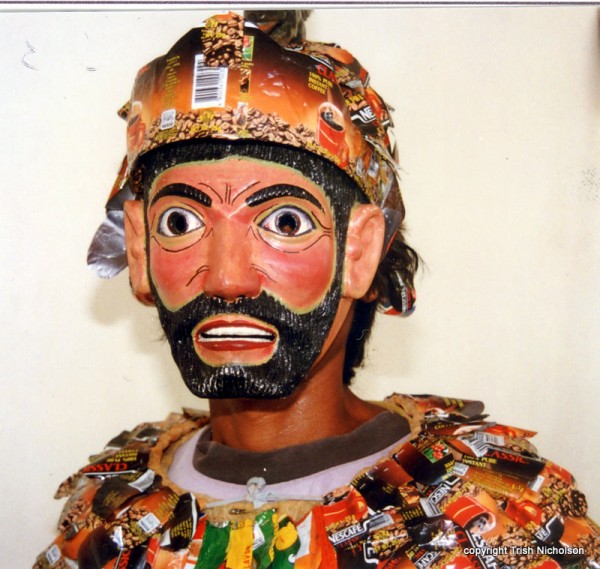

What lies behind the masks of Mogpog? It was me behind this one; carved for me to wear as a penance during Moryonan – the Easter week re-enactment of the Longinus legend.

What lies behind the masks of Mogpog? It was me behind this one; carved for me to wear as a penance during Moryonan – the Easter week re-enactment of the Longinus legend.

If you have been following these tales, you will know that Mogpog is a small town on Marinduque Island in the Philippines. This third tale is about the making and wearing of my mask.

My Moryon mask in bulaklakan style

Long gone are the days when an anthropologist had bearers to set out his canvas chair and pour his unavoidably sun-warmed claret while he observed the ‘natives’, interpreting their customs through the sieve of his own western culture. This on-the-spot empirical method was better than sitting at home imagining hairy little men with tails, as some earlier scholars had done, but was too close to ‘empire’ for long term credibility.

To understand other cultures we must experience them: participant observation is not the only method used but it is a key one. There are still those who insist one should go armed with a ‘theoretical framework’, but to me, a framework is simply a sieve with a different name: time enough to look at theories when I have data to think with. So I went unarmed, to live with a local family kind enough to tolerate my daily mangling of their mother tongue, and generous enough to share their traditions. That is how I came to wear the mask in Moryonan.

There are two different styles of mask. In this photograph are the Roman masks, depicting Roman soldiers during Jesus’ arrest and Crucifixion. Women can be Romans (though not many choose to), but ‘my family’ supported my wish to wear the original, bulaklakan mask, worn since the first Moryonan in the 1860s.

There are two different styles of mask. In this photograph are the Roman masks, depicting Roman soldiers during Jesus’ arrest and Crucifixion. Women can be Romans (though not many choose to), but ‘my family’ supported my wish to wear the original, bulaklakan mask, worn since the first Moryonan in the 1860s.

Bulaklakan is Tagalog for ‘covered in flowers’: it is the headpiece – the turbante – that bears flowers, traditionally seven and usually made of coloured foil. Having made our decision, I was taken to one of the best carvers in town to place my order and be measured up. The impressive result is the mask shown at the top of the page. It is as close as possible to the oldest mask still in use, which was made in Mogpog in 1945. Do you see the little pinwheel in the centre of the turbante? – It twirls in the breeze. That is traditional too, but no one knows why.

Masks are carved by hand from a single block of local softwood called dap-dap (Erythrina subumbrans). Most Moryons make their own masks, but sometimes another Moryon will make the turbante for them. This mask has been carved and sanded, ready for painting.

Masks are carved by hand from a single block of local softwood called dap-dap (Erythrina subumbrans). Most Moryons make their own masks, but sometimes another Moryon will make the turbante for them. This mask has been carved and sanded, ready for painting.

During Moryonan, bulaklakan Moryons represent the Pharisees and others who betrayed Jesus of Nazareth in the Passion story. When not taking part in rituals inside the church, or accompanying processions of saints, Moryons roam the town each day during Easter week as a panata – a vow of penance.

I can attest to the validity of the penance. When wearing a full mask – covering also the ears and extending under the chin – it is difficult to see through the two tiny wide-apart eye-holes; difficult to breathe only through the narrow slit in the mouth, and becomes hot and heavy in humid tropical heat.

Here I am on the left, feeling like a boiled lemon, with a make-do red shift and a borrowed spear, waiting for a parade to start.

Here I am on the left, feeling like a boiled lemon, with a make-do red shift and a borrowed spear, waiting for a parade to start.

The inside of the mask is not sanded and painted but left rough where the wood was chiselled out: where it chafes, your skin stings and itches when sweat pours down your face. Instinctively, you raise your hand to your cheek, feel inanimate wood and realise you can do nothing about it – such are the sacrifices of a dedicated anthropologist.

In recent years, a new style of turbante – the artistic bulaklakan – has become popular. All manner of creative materials are used to make these, including moss, woven string, seed pods, feathers, and even empty Nescafe sachets. (I’ll show you more of these in my next Tale.)

What happened to my magnificent Moryon mask? Ritual masks are not souvenirs; they are significant cultural artefacts. I was reluctant to take it too far from its cultural context, but wary of causing ripples by giving it to one Moryon rather than another – they had all been so encouraging and helpful in my panata – so I gifted it to the Anthropology Department at the University of the Philippines, where I was studying for my PhD. I hope it is still there.

[This is an archived post originally posted in 2011 and based on field research carried out during 1995-7. Some things have changed in Mogpog, but they still celebrate traditional Moryonan, and it is good to record and remember the recent past for future generations.]

Rituals, enactments, street theatre – they are all part of Story’s rich repertoire, along with myths, fables, epics, sagas, legends, folktales and novels, a heritage that has sustained us physically, spiritually and socially since our ancestors were hunters and gatherers. Learn more in this entertaining, global social history of storytelling: A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity.

If you missed the other posts in this series, the links are below:

Travel Tales of Mogpog 1: the Town Band

Travel Tales of Mogpog 2: Society Ladies of Mogpog

Travel Tales of Mogpog 4: More on Masks

Hi Trish, another great post (as usual). I never would have guessed that it’s you in the mask. You definitely go far for your art. I enjoyed this and am eagerly waiting more 🙂

So pleased you enjoyed it, thank you for telling me. There will be more, more masks too, although I’m going to do a couple of different topics first – don’t want reader fatigue 🙂

Amazing and very interesting, Trisha. Must be lovely to be so involved in the event, although the mask sounds very uncomfortable to wear. Really enjoyed.

Jane Isaac

Great post, Trish. The saga continues!