Words matter. Conjured into stories, they are powerful. And after writing systems developed some 5000 years ago and words were engraved into stone as a permanent, definitive ‘truth’, their power became mighty.

Words matter. Conjured into stories, they are powerful. And after writing systems developed some 5000 years ago and words were engraved into stone as a permanent, definitive ‘truth’, their power became mighty.

In cultures worldwide, myths claim fertility as a gift of goddesses, but writing came from gods, its potency controlled by kings and priests. Writing became a tool of dominance with the potential to recast history and command the future. Read the news any day to see that this is still the case.

Until the last few hundred years, women were rarely allowed sufficient education to either read or write literature which, for centuries, was written in elite languages of scholarship: in Europe, Latin and Greek; in Japan and China, classical Chinese; and in India, Sanskrit and Persian. Boccaccio took the innovative step of writing his Decameron in the vernacular specifically so that women could enjoy his delightfully ‘naughty’ stories. But only upper class women were literate.

Little wonder that ‘famous’ women writers in the past are hard to find.

Recognition came to a few. The accolade for the world’s first novelist could arguably be awarded to the tenth-century Japanese scholar, Murasaki Shikibu, for her novel The Tale of Genji. An indulgent father had allowed her to share her brother’s education, though she wisely concealed her mastery of classical Chinese – knowledge deemed inappropriate for a woman.

Another contender is the prolific, seventeenth-century writer, Aphra Behn, for her novella Oroonoko. She was probably the first English author to make a living entirely from writing and, being that unthinkable entity, an independent woman, became the subject of scurrilous gossip in London’s fashionable coffee houses.

Though often now forgotten, Queen Marguerite of Navarre was famed in her time as a humanist poet. Despite her being the King of France’s sister, censors at the Sorbonne tried to destroy her work. For her role in protecting humanist scholars during the bloody years of religious oppression, French historian, Jules Michelet, honoured her as ‘Mother of our Renaissance!’

No one denies Queen Marguerite’s place in history, but we almost lost her short stories. When first issued, posthumously in 1558, her manuscript had been virtually rewritten by a printer who published it as the work of an unnamed male author. Thanks to another printer, Claud Gruget, we can appreciate her original framed story collection to which he gave the title Heptameron, and credited her authorship.

Hidden more deeply are the many women upon whom famous male writers depended. The mothers, daughters, sisters and wives, who critiqued, copied, edited or proofread the works of their menfolk, nursing their egos during life and immortalising their works after death.

Anton Chekhov’s sister, Masha (Maria Chekhova), abandoned her ambitions as an artist as well as the possibility of marriage, to assist his writing and social projects. Support which became more emotionally demanding as tuberculosis condemned her beloved brother to an early death. We owe a debt to Maria Chekhova for the collection and preservation of Chekhov’s huge body of work, a task to which she dedicated the remainder of her life.

Sara Coleridge’s recently discovered poetry indicates the potential she subordinated to the needs of her famous poet father. And though we have only a travel journal written by Dora, Wordsworth’s devoted daughter, Sara Coleridge observed that the demands of Dora’s father “frustrated a real talent.”

Dazzled by the glare of celebrated authors, history too often forgets their mothers. It is well known that Maupassant’s career was launched under the mentorship of Gustave Flaubert. But it was Maupassant’s mother who wrote to her friend, Gustave, urging him to take an interest in her troubled young son.

And when nineteen-year-old Nikolai Gogol escaped provincial Ukraine for the literary highlights of St Petersburg, he discovered that publishers wanted only stories of the ‘Little Russia’ he had disdained. In a panicky letter to his mother, he demanded descriptions of local wedding customs, including ‘the costume of a village deacon, from his underclothes to his boots.’ Without questioning how she might know of the deacon’s underwear, she sent the details – down to the tiniest hair ribbon – that appear in one of Gogol’s first successful stories, ‘St John’s Eve’.

Support was not always literary: the devotion of Edgar Allan Poe’s mother-in-law (and aunt), Aunt Clemm, nicknamed ‘Muddy’, offered emotional anchorage throughout his chaotic adult life as well as finding food for the family in times of dire need.

Sir Walter Scott, who thought Jane Austin a better novelist than himself, noted in his Journal that when it comes to portraying ‘the actual current of society […] the women do this better.’

Aboriginal women in Australia are guardians of bush lore – oral stories vital to spiritual and physical survival – as ancestral Eves no doubt were in our foraging pre-history. Women’s story-power is fundamental.

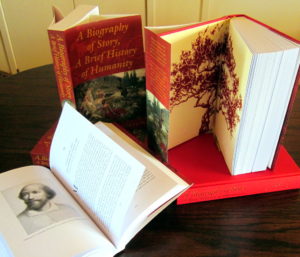

Because A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity traces the power of stories throughout a global history in which women were often invisible, male storytellers outnumber females, but casting a light on women succeeded: the indexer submitted as many subentries under ‘women’ as under other major topics.

[Article written originally as a guest post for Women Writers Women’s Books website]

A Biography of Story, A Brief History of Humanity, the power of stories in the comedy and tragedy of human affairs. A global social history of stories and storytelling. You can read the background to the book here.